Weaver's Week 2009-10-04

Revision as of 12:00, 22 December 2009

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Contents |

"But we don't want to give you that!"

Between now and the end of the year, this column will be looking back over the past ten years of game shows. What you'll be reading is the interpretation of this column, attempting to draw together some sort of pattern where none may exist. Other interpretations of the source material are valid. It's this column's opinion. It is not scientific fact, it's opinion.

| If we're to believe the official records, the first game show event of the 2000s was the National Lottery Millennium Million Maker, when Dale Winton had to go backstage in order to find a machine that was resolutely not going to come out on set. This column reckons the first game show of the 2000s had actually taken to the air sixteen months earlier. In this first part of our review of the decade, we'll be recounting the shows where the love of money was the defining factor. Shows that reflected the decade of casino capitalism: shows that were driven by dough, by greed, by fear. Shows that made a virtue out of vast prizes.

Who Wants to be a Millionaire (1998 – present) was the end of a chain that stretched back through the 1990s. The Conservative government had reduced the regulatory burden on television and radio producers in the early 1990s, and one of the rules swept away was the maximum prize. The IBA had fretted in 1989 lest the Irish-licensed Atlantic 252 attract audiences by giving away huge amounts of money, possibly as much as £1000. ITV began its newly deregulated era by giving away £10,000 cars on Celebrity Squares (1993), then £100,000 houses on Raise the Roof (1995), and within three years had added the last nought for one million pounds, cheque. Though a million pounds was available, it wasn't going to be won easily. In the six runs of Millionaire up to the end of 1999, no-one had won the top prize, no-one had won the half-million, and only a handful of people had faced the half-million question. Though maverick radio DJ Chris Evans had given away a million quid twice in late 1999, the Millionaire top-prize winner was what the nation wanted to see. The chase continued through the spring – Peter Lee will never forget Durham cricket club, Peter Spyrides and Kate Heusser faced the final question, but also walked away. Episode 100 passed in October, and still the prize was unwon. | |

| The chase finally ended on 20 November 2000, when Judith Keppell walked out of the studio a millionaire. The programme quickly lost its lustre, and introduced play-along games and SMS interactivity to keep up its audience. There were other top-prize winners: David Edwards, Robert Brydges, Pat Gibson, and Ingram Wilcox all drew the million out of Chris Tarrant's cash machine.

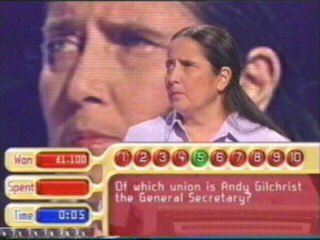

Tarrant was – and still is – one of the greatest hosts on television. He makes a hideously complicated show look effortless, and he is able to talk to the contestants without influencing them in any way. It's a tribute to his great skill, and the simplicity of the format, that Millionaire has remained a regular on the schedules to this day – there aren't a hundred shows a year, as in 2001, but for any prime time show to last eleven years is an achievement in itself. But Millionaire had its seedy underbelly. The programme was financed from premium-rate telephone calls, and there was a long-running suspicion that the producers were weeding out the strongest contestants to encourage others to call. This was never proven, and the evidence for such a conspiracy was basically that no-one had yet won the million-pound prize. No, Millionaire's ethical problems came from its contestants. The story of Charles Ingram has been told often enough, not least in previous editions of this column. Less well-documented was the Daventry Ring, which may have involved help on the final qualifying round, or of people using this new-fangled Internet thing to help answer phone-a-friend questions, in exchange for a cut of the winnings. (See the Weeks of 10 May 2003 and 13 Feb 2005). This wasn't in the spirit of the games, and came to an end after Celador warned the perpetrators off. By then, Celador's next big project had crashed and burned. The People Versus (2000-2) offered unlimited rewards to contestants who were prepared to invest unlimited days in the studio and answer questions on a limited range of subjects. One wrong answer would cost them their place in the game, and the person who set the question would take their place in the next show. But the programmes were painfully slow, the contestants had too many lifelines at their disposal, and the whole experience didn't work. Many of the best bits were recycled for a daytime version, general knowledge questions against the clock, but even that had the unnecessary complication of The Bong Game to disrupt matters. | File:Peopleversus 8.jpg We believe in one more question. One more flip. One more lifeline. |

| The zenith for big-money shows was reached in 2001, when Greed and Shafted had their brief runs on screen. Greed asked players to answer increasingly difficult questions and challenge each other, while Shafted is best-remembered for Robert Kilroy-Silk's iconic hand gesture. Both shows offered bigger jackpots than Millionaire – Greed went up to £2m, and though Shafted's format allowed nine-figure payouts, the producers capped it at £2.5m. Had Greed lasted, we suspect that someone would have walked away with the maximum, but it was never going to come back. Both shows were complex affairs, lacking the simplicity of Millionaire, and neither survived more than a few weeks.

The shows immediately afterwards pretended to have big prizes, but offered other thrills – Saturday Night Takeaway (2002-9) offered the contents of an ad break, but this was nothing more than a hook around which Antan Dec could hang a rather good light entertainment show. Over on the BBC, Come and Have a Go If You Think You're Smart Enough (2004-5) took the premium-rate entry idea, added various technical ideas that were perhaps a little ahead of their time, and almost made a decent interactive quiz out of it. The second series junked much of the technogubbins to leave a solid quiz. Duel (2008) is the only quiz to appear since 2001 that's threatened to give away six-figure prizes with any regularity. It's not the only show that's threatened to give away huge amounts of money. That thread began with In It to Win It (2002 – present), which by dint of being very simple to follow, has proven the longest-running of all the games around the UK lottery. People come up to play, Dale Winton asks them some multiple-choice questions, and the more they get right, the more they stand to win. The top prize of £100,000 has been won a couple of times, and it's clear that everyone – win or lose – is treated well and has a lovely time. How could it not be lovely, Dale's involved. | |

| Deal or No Deal (2005 – present) also gives away six-figure prizes on occasion. Much has been written about this show, how it is little more than a glorified guessing game, and how the host is a complete Noel Edmonds. Here's another way of thinking about Deal: it's a complex skill game, in which there's one permanent player (The Banker), and a transient here-today-gone-tomorrow player stuck in the studio with Little Noely. The viewer isn't privy to The Banker's thought processes, only the reaction of the day's studio guest. Maybe part of the draw is that it's very difficult to get in the mind of The Banker. Especially when the host's ego keeps blocking the view. Maybe that's all part of the masterplan.

Deal has had more than its fair share of imitators. Most blatant was The Colour of Money (2009). It combined the concept of opening boxes (er, starting and stopping cash machines) with the tedium of the bong interlude from The People Versus. Though the show had lots going for it – Chris Tarrant, a phenomenally pretty and well-designed set, ITV's hype machine – the designers forgot to include any game. Daytime pilot The Fuse (2009) took a perfectly good quiz and wrapped it up in some rather pointless box guesswork, meaning that at least one contestant played the ultra-tense final game for the princely sum of ... one pound. That's not even his bus fare home! Three other programmes have given away a million pounds during this decade. We'll address Survivor in a later installment, and turn to the red-haired child of this decade, The Vault (2002-4). Contestants bid to buy answers from players in the studio and on the telephone, with a jackpot game that usually went to a caller at home. One of those callers, Karen Shand, won a million quid from the comfort of her armchair on a hot summer's night in 2004. The Vault's problem was that it was a pale imitation of the Israeli original – there, the show went out live, callers were screened and the contestant knew that they knew the answer. | |

| Antan Dec also gave away million-pound cheques, to Sarah Lang and Dominic Jackson. They were the two winners of Poker Face, a general knowledge quiz that was as much about bluff and bluster as it was about knowing facts. And it was bluff and bluster, rather than knowledge, that would prove to be the defining feature of the second half of the decade. Like Shafted and Greed, Poker Face had attempted to give some sense that the winners had earned the right to progress, by answering lots of questions correctly. Unearned greed had already had some television coverage – Late Night Poker (1999-present) had helped to popularise that form of gambling, and shows like Casino Casino (2002-3) found a home on niche channel Challenge. The fruit machines gave up the luck game Spin Star (2008), while bingo begat The Biggest Game in Town (2001).

These were niche programmes. Golden Balls (2007-9) turned greed into something bizarrely popular. Jasper Carrott presided as grown people lied, shouted, bitched, and generally acted as though they had an entitlement to huge amounts of money, before eventually playing the very same endgame as Robert Kilroy-Silk's show. Though dressed up in huge amounts of shiny sheen, Goldenballs was all about the worst side of human nature. It wasn't about people as people, it was about people as backstabbers. Players weren't removed because they might be a threat, they were removed because other people were worried they hadn't been dealt a good hand. Removal of the unlucky, of the unconvincing. Survival of the nastiest. Fear that someone else might be earning more wasn't confined to the small screen. Out in the real world, bankers were shuffling numbers like so many chips, and their bosses were letting them take home astronomical amounts of money. The gamblers hadn't done anything to earn this dough, it just rolled in through sheer luck but the bosses were worried that if they didn't pay "the going rate", the gamblers would go off and gamble on someone else's dime. Eventually, the bets on black failed, and the whole house of cards came crashing down. | |

| During the mania for business gamblers, television convinced itself that casino capitalists were able to make quality television. The BBC allowed Alan Sugar to promote himself through The Apprentice (2005 – present), all the time trying to conceal the fear that lies at the core of any bully. ITV tried to retaliate with Tycoon (2007), but Peter Jones (3) proved less effective as an advocate for greed. Even the children's department got in on the act, though Beat the Boss (2006 – present) owes more to the world of design than business.

As the crash hit the real world, there was evidence that this glad-handing of big business was offensive – the commentary to Natural Born Dealers (filmed 2007, shown 2008) laughed at its salesmen, rather than with them. The Last Millionaire (2008) sought to find the most inept ego-driven young entrepreneur, and both The Restaurant (2007 – present) and Design for Life (2009) judge on criteria other than pure profit. The business world's greed and fear spread far and wide. During 2005 and 2006, we couldn't move for call-and-lose quiz programmes. These shows asked questions more obscure than they appeared, waved big cash prizes, and almost demanded that viewers call in lest someone else win that dosh. The real winners were the promoters, who would take 50p from every call, and only let a very few callers through to air. | |

|

It was a bubble economy, and like all bubbles, it was going to burst. It went in spring 2007, and splattered almost everyone. Richard and Judy's chat show was the first scapegoat, then we heard that GMTV was picking winners before the lines had closed, Gameshow Marathon and Dancing on Ice had votes going missing, Deal or No Deal's legalised telephone lottery proved to be less than legal, a handful of BBC competitions had been pre-recorded. And it went on, and on, and on. Three examples of blatant and premeditated deception stand out. Antan Dec had asked for callers from anywhere in the country to play on the Jiggy Bank, but had already determined the broad location from which their winner would be picked. Their Gameshow Marathon (2005) awarded prizes based, in part, on how the researchers thought the contestants would react on screen. Then there was Endemol, who regularly invented winners to its Brainteaser (2002-7) programme, putting a member of staff on air if the first two people it called gave a wrong answer. (Weeks of 1 July and 21 October 2007). In neither of these cases was there a concerted attempt to prevent prizes from being given away. Even this figleaf was absent from GCap's Secret Sound competition, where an instruction from management was interpreted as "don't let anyone win the competition", and losing entries were deliberately selected to go to air. GCap attempted to cover up its tracks, offered inconsistent explanations to the regulators, and was fined over a million pounds. (Week of 29 June 2008) The first programme to cover its prize costs through premium-rate phonelines was Millionaire. Abuse of this system brought it crashing down into an unpopular heap, and the regulator has effectively banned the use of premium-rate phonelines to raise revenue. It would be difficult to make Millionaire in that way now, people were just too greedy and didn't know when to stop. |

Coming in two weeks, part two: "Who should be voted off the team?"

University Challenge

Heat 12: York v St George's London

| Another evening of gentle exercise and quiet desperation for the students, during which they'll be asked about 100 questions. And get about half of them wrong, if past performance is anything to go by. The sequence begins with a missignal on the Word of the Week starter, "zombie". It's correctly answered by York, an institution first suggested by James I. A mere 346 years elapsed before the government got round to authorising it, which just shows what happens when people submit their plans in triplicate on green, and not yellow, paper. Alumni include the authors Anthony Horowitz and Graham Swift.

At the third starter, St George's London get going. This institution was established in 1733, and famous students include Patrick Steptoe and Edward Jenner, whose cow innocculated against cowpox is on display in the library. Though Thumper doesn't mention it, the college is a medical college, and all four members say they're studying medicine. Bit of a giveaway, there. The first visual round is on the wives and girlfriends of world leaders, as seen at the G20 photo-opportunity in London earlier this year. Neither team gets it, and York has a 30-25 lead. The visual bonuses eventually go to St George's, where they confuse Mr. Rudd, the prime minister of Australia, with Miss Tyrynenko, the prime minister of Ukraine; and have no idea who Mr. Hu of China is. Magic circles also evade the medics entirely, and disallowing "Diego Garcia" for the "Chagos Islands" is a bit harsh in our reckoning. | |

We'll take Embarrassing Answer of the Week:

These people are medics? Take us to the audio round, which is basically asking "who wrote The South Bank Show's theme music?" The bonuses continue in this vein, and though the medics know it's The Apprentice, they don't know it's Prokofiev. From Romeo and Juliet, fer cryin' out loud. St George's leads 95-25. Another physiology question goes to the medics, but they're less good at royal abdications, not even answering Austria-Hungary at the right time. Now, were any of the team watching Panic Attack over the summer? If they were, they'll have recognised the question asking for cities with a single letter as their postcode. Another visual round, and it's a detail of a painting. Some obscure painting called the "Mona Lisa". It brings York back into the game, and they trail by 135-40. | |

| St George's respond by getting the first full set of bonuses all night, and it confirms they really can't be caught. Especially if they waste time repeating bits of the question back at the host. York do get back in the game, but suggest that the Tees flows in Staffordshire, not Yorkshire. Do they not remember Tyne Tees Television? They're only 19, so no. Impressive starter asks after the US space programme named after its two-man crew, but it sails about 200 miles over the team's heads. At the gong, St George's has won by a convincing margin, 200-55.

Meriel Whalan was best on the buzzer for York, getting two starters: the team managed 4/12 bonuses with one missignal. Charley Tinsley (six starters) banged well for St George's, their bonus rate was an unconvincing 14/39 with two missignals. With four starters dropped by both sides, there were 36/73 questions right, slightly less than half marks. Next match: St Andrews v Somerville Oxford | Repechage standings:

|

Mastermind

Heat 6

Chloe Stone starts us off this week with the Cazalet books of Elizabeth Jane Howard. They're a quartet of books about the Cazalet family, set during the Second World War. The contender says her revision has mostly been re-reading the novels. And why not. As ever, lots of questions about small details, which feels reasonable for such a small subject. After what feels like a very long two minutes, the contender finishes on 14 (5).

Shaun Deehan is going to tell us about the Life and Times of John Hume. There are a number of John Humes in our purview: this one is the Northern Ireland politician (1937-), the leader of the SDLP and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. There's a hideously convoluted question about the number of the amendment (and not the original article, as the contender thought) to the Irish Constitution vowing to bring about a united Ireland by peaceful means. That sort of minor detail keeps tripping up the contender, who ends on 9 (2).

Ron Ragsdale discusses Egyptology, and he states that they invented such concepts as the rule of law and the date. His round seems to go at a very slow pace, and there are a number of passes as the round draws towards a close. The final score is 8 (4).

Our final contender is Joe Docherty, taking British New Wave cinema. This was a set of films made circa 1960s, and was move away from the upper-class concerns of film to this date. They're kitchen sink dramas, like "Look Back in Anger" and "Room at the Top", according to the questions. It's a good round, with a decent guess at the end, and just enough for the lead – 14 (0).

Is it BBC cross-promotion to ask about the winner of the Formula One races? Perhaps not, it was a good question when ITV held the rights. Ron Ragsdale gets that question, and the Minister of Silly Walks, to finish on 14 (8).

Shaun Deehan clearly remembers the old standby on Blue Peter, papier-mache. We wonder if Humphrys is getting wise to the old Mastermind standby of only giving the surname of a person, as he repeats with the given name as well, thus negating any time saved. He ends on 20 (6).

The repechage:

- Les Morrell 26 (3)

- Colin Wilson 25 (0)

- William de Ath 25 (4)

- Vishal Dalal 23 (4)

- Joe Docherty 22 (5)

- Mike Hely 21 (5), Adam Lister 21 (5)

Chloe Stone gets a hideously long question about what a bride should wear on her wedding day, but it's the first of a lot she gets right. We're particularly impressed with the way she dredged "orchids" for a question about vanilla. The final score is 26 (8), which – at the very worst – will put her on the repechage board for a very long time.

Realistically, Joe Docherty needs twelve to win, eleven to stand a good chance of coming back. Though he misses the first question, it feels as though he's going to sail through this round. However, a series of passes in the middle of the round holes his chances of winning, and the final score of 22 (5) may not quite suffice. The final question deserves a very quick discussion: Stade Francais is the team playing its rugby at the Stade de France.

This Week And Next

Leafing through the rusty old Radio Times, we came across some good news regarding Only Connect. The champion-of-champions match be shown later in the year, and the writer had a sly dig at BBC4 for daring to put on something decent in the summer, when no-one else bothers. There's also set to be a new series of everyone's favourite quiz in 2010. Of course, no mention of The OC would be complete without a picture of the star of the show, but readers of the BBC's official organ had to make do with one only showing Victoria Coren.

Even now, the phone voting scandal's not quite dead – OFCOM has fined Channel TV £80,000 over voting in the British Comedy Awards of 2004 and 2005. Both years, the "People's Choice" award was presented during the News at Ten Thirty, but votes were still sought when the show resumed at 11. In 2005, the most votes were received by Catherine Tate, but the award went to Antan Dec. On the latter matter, Channel said it wanted the police to investigate, as there may have been a fraud against the public. The British Comedy Awards was independently produced by Michael Hurll Television Ltd, and OFCOM noted that the information it had received from parties other than Channel was insufficient for it to establish exactly what happened.

The format tombola has been spinning again, and it's stopped on the infamous Making A Cup Of Tea game from The Mary Whitehouse Experience. Having to make a show along those lines is NBC (America, not Japan), and they want people to perform ten household chores to standard in less than a minute. What they've got to do is put the teacup inside the teapot...

Ratings for the week to 20 September have been published by BARB. Strictly returned, with 8.9m viewers on the Friday night, and slightly fewer on Saturday. Simon Cowell Annoys had 11.35m viewers on the Sunday, 10.5m on Saturday, suggesting that the people of Britain voted with their remotes. Celebrity Fortunes was seen by 5.75m, The Cube 4.85m. Millionaire's 3.4m puts it only slightly ahead of University Challenge (3.05m). Masterchef The Professionals came back with 2.9m, and Mastermind continues to improve, 2.05m excluding Wales. It's only a sneeze behind Come Dine With Me.

Low ratings all round on the digital tier: a round 1m for More Annoyance, 845,000 for Come Dine With Me, and 785,000 for a repeat of Cowell's show. There are 450,000 viewers for Hell's Kitchen Us, and the 190,000 for Strictly on BBC-HD put it on a par with another light entertainment veteran, Basil's Game Show. We'll cheer for Mastermind Plant Cymru, 43,000 on S4C is a the best game show rating on that channel all year.

Coming next week, we've reviews of The Big Food Fight and of Clever v Stupid. Before then, Keep Your Enemies Close comes to BBC1 (4.05 Friday), there's a new series of The Unbelievable Truth (Radio 4, 6.30 Monday), Banzai pops up on Dave (11.20 Friday), and Bruce Goes Dancing (BBC1, 4.20 Saturday) to prove his public service credentials. Simon Cowell will be celebrating his birthday this week.