Who Wants to be a Millionaire?

Contents |

Host

Broadcast

Celador for ITV, 4 September 1998 to 28 July 2007

2waytraffic for ITV, 18 August 2007 to present

Synopsis

Well, it had to happen at some stage, but perhaps even we didn't expect this go-for-the-throat show to be such a huge success. The previous unconvincing "let's raise the stakes" show, Raise the Roof, was still fairly fresh in the memory, and this new show might have been just the same but with an extra "0" on the end of the budget. Thankfully, not so.

The timing

However, there were a few things that were intriguing before the programme was even broadcast which made things look distinctly promising. The major clue that something special was on its way was that ITV was clearing some cupboard space for this baby. The idea was that the programme would appear at roughly the same time every night for 12 consecutive days, bulldozing through whatever scheduled episode of Inspector Wexford or The Bill was supposed to appear there instead. Good grief, even the ITV golden goose of Coronation Street was once rescheduled because of it!

The rules

Ten contestants from around the UK take part in each programme. From the ten qualifiers, one contestant is chosen via a timed question. This contestant plays for the £1,000,000 top prize.

The contestant must answer 15 multiple-choice questions correctly in a row to win the jackpot. The contestant may quit at any time and keep their earnings. For each question, they are shown the question and four possible answers in advance before deciding whether to play on or not. If they do decide to offer an answer, it must be correct to stay in the game.

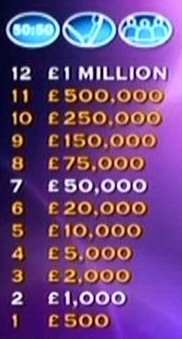

The money tree. Currently, this contestant is at £500. Answering the next question correctly earns them a guaranteed £1,000 - no matter what happens thereafter.

The money tree. Currently, this contestant is at £500. Answering the next question correctly earns them a guaranteed £1,000 - no matter what happens thereafter.If at any stage they answer incorrectly, they fall back to the last "guarantee point" - either £1,000 or £32,000 - and their game is over. For example, a contestant failing on question 13 would win £32,000. Answering incorrectly before reaching the first guarantee point (£1,000) loses everything. A new player is picked from the remaining pool of 10. If time runs out on a particular programme, the next programme continues that player's game.

When the money starts getting really serious (£32,000 and over), the host will reach for the appropriate cheque and sign it. Whilst this is mainly used as a theatrical device, the cheques can be cashed in by the contestants for real.

Lifelines

At any point, the contestant may use up one (or more) of their three "lifelines". These are:

- 50:50 - two of the three incorrect answers are removed. Originally, these answers were chosen in advance by the question-setters (and so would invariably be the two you knew it couldn't be), but this was later changed to a random selection.

- Phone-A-friend - the contestants may speak to a friend or relative on the phone for 30 seconds to discuss the question.

- Ask the audience - the audience votes with their keypads on their choice of answer.

Each lifeline may only be used once during a contestant's entire game.

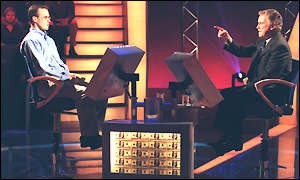

A Phone-A-Friend in progress.

A Phone-A-Friend in progress.The host

Chris Tarrant (pictured) is one of those game show hosts whose job it is not just to get up your nose, but to tickle your nostrils and play with the nasal hairs while he's in there. He has perfected the art of getting people to scream "WILL YOU JUST DAMN WELL GET ON WITH IT!" at the radio through his years of running promotional games on Capital FM (his 9-to-5 job is a disc jockey - shouldn't that be 6-to-10 job?)

Millionaire maker, Chris Tarrant.

Millionaire maker, Chris Tarrant.While Who Wants... was a very simple idea, it needed a good host to carry it off and Tarrant was that host. For example, if the producers had plumped for Richard Madeley, Les Dennis or even Brucie it's almost certain that the ITV audience wouldn't have been anywhere as captivated.

Tarrant's style was essentially his usual zany/wacky persona, but unusually in this game he showed that he could be professional and accurate when the need arose (e.g. when reading out the initial qualification question, where time of response was critical). Yes, he was annoying when he took about a minute before telling the contestant know that they had now won "...X THOUSAND POUNDS!!!", but that's the point - no-one else in the business could have built up this suspense. He made you care.

Marks for style and technical merit

Putting the easy-to-pick-up format and the host aside for one moment, it's clear that some T.L.C. went into the making of the show. In fact, the whole theme of the programme seemed to take the essential classic elements of a quiz but present them using modern metaphors. For example, the synthesizer fanfare theme music was dramatic, but if you listened closely you could make out more than a passing semblance of the actual famous "Who Wants to be a Millionaire?" song - so famous, we can't remember what film it appears in. [High Society - Ed.] There was even some extremely nice Pet Shop Boys-esque background music while the contestants pondered about the questions, with deep, gothic-sounding choirs intermixed with high-pitched electronic arpeggios. The entire musical score is even available on CD (see Merchandise below).

The famous Who Wants to be a Millionaire? set, based in Elstree, London.

The famous Who Wants to be a Millionaire? set, based in Elstree, London.The set is one of those "in the round" numbers. Perhaps not the most original idea in recent times, but it's so nicely constructed (with its suspended Perspex floor with a huge dish-shape underneath covered in mirror paper) you could tell Terence Conran would approve.

The lighting also deserves a passing mention, with the spotlights zooming down on the contestant after each major question answered. Even the logo is smartly and wittily executed, mixing the traditional intricate bank note patterns with question marks and pound signs.

What happened?

Scenes like nothing else in recent quiz show history took hold when WWTBAM? was first broadcast. Towards the end of the first series, it was bringing in more than 18,000,000 viewers. It even beat some editions of the perennial ITV ratings stalwart, Coronation Street. The show deserved these ratings though - it wasn't just any old quiz.

The first millionaire

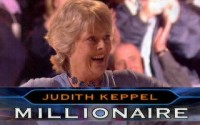

After 122 programmes, Judith Keppel became the first person to answer all 15 questions correctly in the original UK version of the show. Allegations of a fix (unsubstantiated, to our eyes) raged in the newspapers because the episode happened to coincide with the final ever episode of the popular situation comedy One Foot in the Grave on rival channel BBC 1.

Judith Keppel becomes £1,000,000 richer

Judith Keppel becomes £1,000,000 richerThe question Judith answered to win the money was:

Which king was married to Eleanor of Aquitaine?

A: Henry I

B: Henry II

C: Richard I

D: Henry V

Judith correctly answered B. Because of the pound's exchange rate, her win was the highest ever win on the quiz show anywhere in the world.

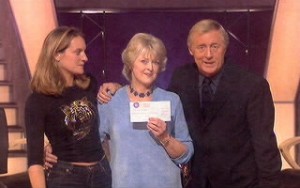

Judith holds her cheque with her daughter (left) and Tarrant (right).

Judith holds her cheque with her daughter (left) and Tarrant (right).Despite the big win, there's no doubt Chris Evans spoiled the party a little by beating Tarrant to giving away £1,000,000 on air. His Channel 4 TFI Friday entertainment show gave away £1,000,000 in a spoiler slot during December 1999 called Someone's GOING to be a Millionaire (subtle, no?), which wasn't a patch on the real Millionaire except in one regard - namely, there was a guaranteed payout.

Millionaire has opened many doors for British TV producers. With this show now signed up to over 100 countries, there's no doubt that the world will be watching the television emanating from this fair land more closely in future.

Regis Philbin (right), host of the US version, tells John Carpenter (left) that he is the first millionaire of the US series.

Regis Philbin (right), host of the US version, tells John Carpenter (left) that he is the first millionaire of the US series.A new beginning, or the beginning of the end?

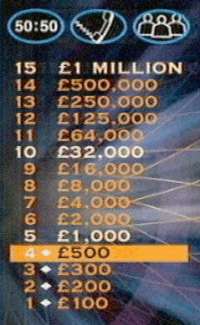

On 18 August 2007, Chris Tarrant's world turned upside down as the format - one of the few things that hasn't changed in all these years - was altered significantly. The first three easy peasy questions were gone and a new - decidedly odd - money ladder was put in place: £500, £1,000, £2,000, £5,000, £10,000, £20,000, £50,000, £75,000, £150,000, £250,000, £500,000, £1,000,000. The theme music was seemingly remixed for a nightclub, though gone is the gold standard think music to be replaced by some decidedly average bangs and thumps. The new titles were welcome, the new question graphics are OK but gone is Mark van Bronkhorst's lovely Conduit font to be replaced by, of all things, Verdana. Truly this is a Millionaire for the Microsoft Powerpoint generation.

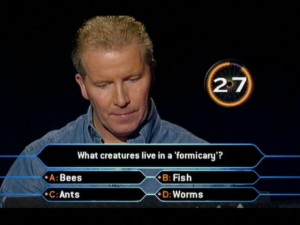

From 3 August 2010, more changes were introduced to the format, starting with the scrapping of the "Fastest Finger First" round. Instead, contestants were chosen through an off-screen audition process. During the game, if a player reaches the £50,000 level, a new lifeline becomes available to them called "Switch", which allows them to swap a question they were unsure of for a different one. Finally, and perhaps the biggest change, was the introduction of a time limit on questions. Contestants are now given 15 seconds to answer questions up to the £1,000 level and 30 seconds to answer questions up to the £50,000 level. The last five questions are untimed.

Key moments

When Judith Keppel won the £1,000,000 jackpot, the pyrotechnics man (who'd been sitting in on every show since the beginning of the series) whose job it was to set off the foil streamers pressed the button and... nothing happened. This is despite several rehearsals that the director had carried out in previous weeks and months to ensure everything went smoothly when the big day came along. So instead they tried again (successfully) at the end of the programme.

One of the show's most memorable episodes came in January 1999 when two contestants won £125,000 on the same show. Martin Skillings, a quantity surveyor from Brancaster, became the first person ever to break the £100,000 barrier, only for Ian Horswell - the very next contestant - to repeat the feat around 40 minutes later. This produced a world record at the time for the most money given away to one contestant on a game show. It also produced the world record for the most money given away in a single episode (£266,000).

On the show after Judith Keppel's £1,000,000 win, the Fastest Finger First question was "Starting with ‘Stop’, put the traffic light sequence in order according to the British Highway Code." It turned out that none of the contestants got the right answer. Another question was played instead about Roman Numerals, to which the contestants further demonstrated their thickness in that only one got it right!

Not one of the show's highest winners in terms of money, but certainly one of the most effervescent was Fiona Wheeler, famous for her wish to bathe in a bath of chocolate (something she later did do in a TV Times photo shoot). The question that won her £32,000 (What is the everyday name for the trachea?) was a gift - she happened to be a fan of the medical drama series Casualty.

Fiona Wheeler.

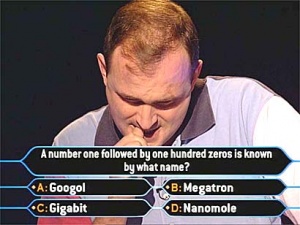

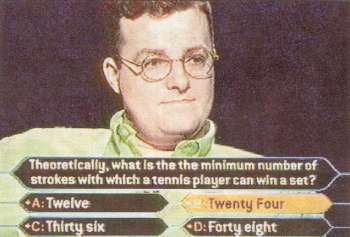

Fiona Wheeler.On the episode aired on 8 March 1999, Tony Kennedy, a warehouseman from Blackpool, was asked the following question for £64,000:

After some deliberation, Tony decides he will play. He offers the answer B, which is locked away into the computer.

After some deliberation, Tony decides he will play. He offers the answer B, which is locked away into the computer.The computer told Chris Tarrant that the correct answer was indeed B, and Tony also went on to win £125,000 by answering the next question correctly.

However, minutes later viewers began ringing ITV and the newspapers to complain. It turns out that the answer to the question is A (12). This is because you could serve 12 aces to win games one, three and five, then your opponent could double-fault 12 times, so you win games two, four and six without hitting a shot and hence win the set after 12 shots.

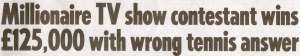

This blunder made front-page news, and the next day an apology was broadcast. Tony was allowed to keep his money.

"FAULT!" ran the front page headline of the Daily Mirror the next day. Incidentally, the Mirror is the arch-rival of the Sun, the newspaper sponsoring the programme at the time.

"FAULT!" ran the front page headline of the Daily Mirror the next day. Incidentally, the Mirror is the arch-rival of the Sun, the newspaper sponsoring the programme at the time.There was a comedy moment came when a contestant, on receiving the £32,000 cheque, scrunched it up and threw it across the studio. He did however have to walk across to pick the cheque up as he subsequently gave an incorrect answer.

On a Valentine's Day celebrity special shown on 11 February 2006 (which is not Valentine's Day), Laurence and Jackie Llewelyn-Bowen (playing for the Shooting Star Children's Hospice) reached the £1,000,000 question. They were asked: "Translated from the Latin, what is the official motto of the United States?" The Bowens went for 'In God We Trust', and in so doing lost their charity a stonking £468,000, the correct answer being 'One Out of Many', from the Latin 'E pluribus unum'. However! It was later decided that the question was ambiguous, since 'In God We Trust', while not from any Latin source, is used as a motto for the US. In fact 'E Pluribus Unum' was never codified by law, and was only a de facto motto until 1956 (when 'In God We Trust' took over), so technically there is no correct answer to that question. So Laurence and Jackie were given another £1,000,000 question ("Who was the first person to go into space twice?") which they did not attempt to answer, leaving with £500,000. The oddest thing about the whole affair was that the incorrect question was broadcast, despite the fact that the error had come to light before the show was due to be transmitted.

And then of course, there was the Major Charles Ingram affair, which is covered in depth elsewhere on this site.

On a celebrity edition in 2007, Rick Parfitt and Francis Rossi from Status Quo said there were two knights on a chess board, when the correct answer is four. However, the game was restarted when producers claimed that the question had been used on the programme before. (That personal mates of Chris Tarrant had bombed out on question one had nothing to do with it, presumably.) They went on to win £50,000 for their chosen charity, the Music Foundation.

One contestant was asked the question "What was the middle name of playwright Richard Sheridan?" The contestant gave the answer Butler, which was deemed incorrect (with the correct answer being Brinsley). However, it turned out that Butler was in fact Sheridan's second middle name, and so the contestant was invited back a few weeks later.

Another contestant was asked the question "Which mythical person shares their name wih a type of insect?". The contestant gave the answer Goliath (which was correctly accepted) - however, one of the other choices was Hercules (which is also correct).

Catchphrases

"Is that your final answer?"

"...but we don't want to give you that!"

"Or you could ask the audience... who are nearly always right"

Inventor

The format was devised by David Briggs, who also devised many of the promotional games for Chris Tarrant's breakfast show on London radio station Capital FM, along with comedy writers Mike Whitehill and Steve Knight. The same team also brought us Talking Telephone Numbers, Winning Lines and The People Versus. The Fastest Finger First round bears a remarkable similarity to a round from a much earlier Celador/Tarrant show, Everybody's Equal.

Theme music

The much-lauded music, which runs almost continuously throughout the whole show, was written by Keith and Matthew Strachan in ten days after it was decided that the music in the pilot show (composed by Pete Waterman) wasn't good enough.

The 'Time's Up' cue is a French horn glissando played by three French horns. So now you know. There are over 100 other different music cues.

The 2007 rave-alike remix was done by Ramon Covalo.

Trivia

The lifelines were originally going to be called "helping hands".

The original promotional trailer featured a fake game show called "Win a Wok", with Chris Tarrant in the foreground explaining the show's concept. He also said "you can phone a friend, ask the audience or even ask me for help". However, asking the host for help never developed into the shows rules.

In the first series, if anybody was struggling in the early questions Chris would give a clue to the answer for the contestant to save their lifelines such as "I don't know but B looks good". This also gave indication to Chris seeing the answer when the question appeared. This led to future shows saying the answer won't appear on his screen until the contestant says "final answer", thus forcing the contestant to use their lifelines early.

Originally, the money tree involved 20 questions ranging from from £10 to £5,242,880 (2^19 x 10). They also considered structures for £25 to £13,107,200 and £100 to £52,428,800. However, later audience research showed that people liked the concept of being a "millionaire" most and so the top prize was actually reduced.

Later on in the format development, the intended idea was for the contestants to start at £1 and answer 21 questions. However, ITV entertainment boss Claudia Rozencrantz through that idea was too boring so they started at £100 in the final format.

When Chris Tarrant hosted the Capital breakfast radio show, he was commuting between central London, the WWTBAM studio in Wembley (or Elstree) and his home in Surrey. As such, he'd only get a few hours sleep a day. He had a second bedroom in the studio so he can get some kip before rehearsals.

WWTBAM is the only UK game show to have been honoured with a postage stamp. It is one of six ITV programmes featured in a set issued in September 2005 to mark ITV's 50th birthday.

Via the US version, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? producer Paul Smith (no relation to the fashion designer) brought such good ratings to the otherwise flagging ABC channel that it was said he was held in such high esteem in the Disney-owned network that he was second only to Mickey Mouse.

If you go to Disney-MGM Studios in Florida, you could (until 2006) play Who Wants to be a Millionaire? live in a mock studio for a chance to win a cruise - and anyone can win! The youngest person ever in the chair was two years old.

Up to and including 8 June 2010, 26 series and 555 episodes have been transmitted.

In the first 25 series, 1178 people have sat in the hot seat, winning a total of £50,762,000 - an average of £43,091 each.

There have also been 270 celebrities competing, winning a total of £6,431,000 for charity.

Nine celebrity contestants have played both the 15 and 12 question formats within the shows history. Eamonn Holmes (with Sir Alex Ferguson in 2004 and Kay Burley in 2007), Piers Morgan (with Ann Widdecombe in 2006 and Emily Maitlis in 2007), Judith Chalmers (with £1 Million winner Robert Brydges in 2003 and her son Mark Durden-Smith in 2008), Penny Smith (with Andrew Castle in 2004 and Anneka Rice in 2009), Jo Brand (with Ricky Tomlinson in 2004 and Nick Hancock in 2009), Andrew Lancel (with Kika Mirylees in the 2004 Cops and Robbers special and Gary Lucy in 2009), Angela Rippon (with Dermot Murnaghan in 2004 and Martin Lewis in 2009), Sir Terry Wogan (with Tim Radford in 2005 and Chris Evans in 2009) and Gabby Logan (with Ally McCoist in 2002 and Katherine Jenkins in 2010).

Olympic rower Sir Steve Redgrave and wife Lady Ann Redgrave originally appeared on a celebrity edition in 2001 but failed to win Fastest Finger First on three attempts. They finally managed to reach the hotseat, six years later, winning £1,000. This also happened to Emma Forbes. She appeared on the same celebrity special in 2001 (with her father and actor Bryan Forbes), also failing to win Fastest Finger First. Emma managed to reach the hotseat in 2010 with Andi Peters.

In rehearsals, Sir Terry Wogan and Chris Evans managed to reach £1,000,000 but ending up winning £1,000 (losing £4,000) on the actual recording.

There have been five £1,000,000 winners – Judith Keppel, a garden designer from Fulham who won £1,000,000 on 20 November 2000; David Edwards, a teacher from Staffordshire on 21 April 2001; Robert Brydges, a banker from London on 29 September 2001; Pat Gibson, a software developer from Wigan on 24 April 2004; and Ingram Wilcox, a civil servant from Bath on 23 September 2006.

The most money lost on the show - and also the greatest loss on a UK game show - was £218,000, by Duncan Bickley in October 2000 when he got the £500,000 question wrong and left with £32,000. On 11 October 2003, Rob Mitchell took the same gamble and also lost £218,000.

Seven people have had a look at the £1,000,000 question and decided to leave with £500,000 – Peter Lee in January 2000, Kate Heusser and Jon Randall in November 2000, Steve Devlin in January 2001, Mike Pomfry in March 2001, Peter Spyrides in October 2001, and Roger Walker in February 2002.

Eight people have left with no money at all – John Davidson in January 1999, David Snaith in March 1999, Michelle Simmonds in February 2001, Peter and Valiene Tungate on a couples show in March 2001, Martin Baudrey on the live 300th programme in November 2002, Bill Copland in April 2004 and Dave Scholefield in January 2005.

The highest ratings were recorded in March 1999 when 19,200,000 people tuned in to watch the unfolding drama.

The show's format has been licensed or optioned to 109 countries. The 100th country to go on air was Kenya. An unexpected spin-off from the international success of the format was that the Indian version inspired an award-winning novel (Q & A by Vika Swarup) which in turn spawned the BAFTA-winning, Oscar-winning, everybloomin'thing-winning hit movie Slumdog Millionaire.

A special live edition marked its 300th show, where Ask the Audience became Ask the Nation, and over 250,000 phone calls were received in less than two minutes.

The Who Wants to be a Millionaire? board game sold more than 1,000,000 units during the first two years on the market.

Not only has the show been voted one of the top five game shows not once but twice by the esteemed readers of this very site, it was also named the nation's favourite game show in a 2008 survey for Churchill Insurance, and again in 2009.

Merchandise

WWTBAM - Edition II Board game

WWTBAM - Edition II Board game WWTBAM Junior Board game

WWTBAM Junior Board game WWTBAM computer game

WWTBAM computer game WWTBAM computer game - 2nd edition

WWTBAM computer game - 2nd edition WWTBAM computer game - Junior edition

WWTBAM computer game - Junior edition The UK Soundtrack album The complete music score for the show on CD

The UK Soundtrack album The complete music score for the show on CD WWTBAM Quiz books

WWTBAM Quiz books Behind the Scenes at "Who Wants to be a Millionaire?" Book by Tom McGregor

Behind the Scenes at "Who Wants to be a Millionaire?" Book by Tom McGregorWeb links

ITV's Millionaire site including online application form

Series 3 - results listing (incomplete)

Results from recent series available on the official site

Pictures

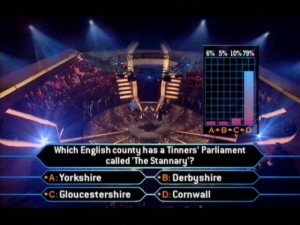

Picture 1 - After an Ask the Audience lifeline, the crowd seem pretty sure the answer is D.

Picture 1 - After an Ask the Audience lifeline, the crowd seem pretty sure the answer is D. Picture 2 - The screens and keypads used for the Fastest Finger First round.

Picture 2 - The screens and keypads used for the Fastest Finger First round.Applications

Prospective contestants should visit http://millionaire.itv.com/beacontestant.php for details of how to apply.

Application details are provided as a service to readers, but please note that all contestant enquiries should be directed to the named production company and not to UKGameshows.com. Addresses can be found on our list of contact details for production companies.