Weaver's Week 2019-07-21

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Previously, we've described Alex Trebek's career – his work at the CBC, and as the host of various daytime quiz shows. Some of them were fun, like High Rollers. Some of them were ahead of their time, like Pitfall. Some of them were just faffy, like Battlestars.

By early 1984, Alex Trebek had demonstrated he was a versatile host. He was best at fast-moving trivia, and at home in academics. He could do the celebrity panel show, and he was great at making complicated formats feel easier. And then, he was approached for what would become his signature role.

Contents |

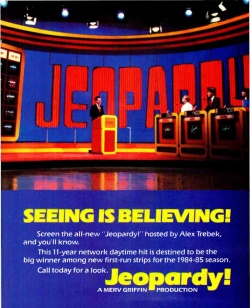

"A game show hosted by Alex Trebek since 1984"

"What is Jeopardy!?"

After the quiz show scandals in the 1950s, North American networks were leery of quizzes. Too easy to give favoured contestants the answers and rig the game, as happened on Twenty-One. So they came up with a novel idea: give *everyone* the correct answer and make players write their own questions. (OK, not so novel: it had been the conceit of 1941-2 show CBS Television Quiz. But no-one remembers that.)

The original series of Jeopardy! ran on NBC from 1964-75, with a brief revival in 1978. The second revival, which started in 1984, was more successful. Alex Trebek stepped behind the podium, and put down roots.

The basic idea is simple – "everyone's favourite answer-and-question show" where they supply the answers, and the players need to give a question that leads to the answer. For instance:

- A: "4-letter play about 9-lived creatures"

- Q: What is Cats?

Answers – or questions – are arranged into categories, and get harder as the round progresses. Points for the correct answer, but the jeopardy is that points are deducted for an incorrect answer. After the first board is completed, or time is up, they play Double Jeopardy!, where all the points are doubled. The show finishes with Final Jeopardy!, one answer where the players write down their answers, and however much they want to wager. Highest score after this final round wins the cash amount indicated.

There are other motifs: the "Daily Double", an opportunity for a contestant to increase their score. "The Clue Crew", assistants who get out and about into the world, to show there is life beyond the studio. And the Final Jeopardy! music is a standard tune to measure out 30 seconds, as familiar and iconic as our Countdown tune.

Jeopardy! quickly proved to be a great fit for Alex's wit and charisma, and he was often able to explain why a particular response wasn't quite right, or when the contender had stumbled into a trap set by the question-writers. "Blessed are the meek? No, it's blessed are the peacemakers."

Inevitably, there have been changes as the years progress. In 1984, contestants walked across the studio to reach their podium, but now walk on from the other side. The early players were able to ring in while Alex read out the answer, something they quickly put a stop to. They gained a strip of lights to show how much time was left to give a response. Originally, winning contestants were capped at five wins, but that rule was revoked early this century.

"That's one thing about Jeopardy!, we're educational as well as entertaining."

"It is incredibly difficult to develop an entertaining game show format that is sustainable over time," said Jonathan Goodson (son of Mark Goodson) in 1993. Perhaps he had the ten-year life cycle of the best Goodson-Todman productions in mind. Jeopardy! has topped that, completing 35 years on television.

What's the secret of success? Consistency. It helps to have the same host for all this time, and it helps to know roughly what you're getting out of each show. Jeopardy! will offer trivia questions with your smart uncle, Wheel of Fortune offers that spinny thing and word puzzles, The Price is Right does its own thing.

While there have been cosmetic changes over the years, the heart of Jeopardy! has been constant. The questions, and the contestants, and the love of knowledge we've seen throughout Alex's career. The contestants have their moment in the sun, their twenty minutes of fame, but we all know the star of the show.

Jeopardy! enjoys some high-quality questions, meticulously researched and fact-checked. Alex Trebek goes through every clue of every show himself, in part to make sure that he can get all the pronunciations right, but in part to make sure he's not going to be talking gibberish on network television.

Because of its longevity, Jeopardy! has become an integral part of the North American culture, something that everyone knows on sight. Pre-school entertainment Sesame Street can riff off the idea, with Alex Trebek playing himself; he's been on telly since before many mothers were born.

For the slightly older crowd, Arthur takes part in "Riddle Quest", a really cool game show where kids answer riddles and win big prizes. Alex Trebek hosts, and stars as himself. As with all episodes of Arthur, there's a life lesson told through the story: in this case, it's to do something because it's fun, and not because all of your friends expect you to.

And because it's been on television for decades, Jeopardy! can be an unspoken reference point. On Rugrats, mother Didi Pickles goes on a different game show. The host reminds her, "...and you don't have to put your answer in the form of a question."

The show attracts celebrity cameos. High-profile celebrities give recorded clues. There are celebrity editions, and – in spite of the high stakes – it's all done in a spirit of camaraderie. Friendships are made, and reunion tournaments turn into chat on old times. The biggest winners become stars, even the daily winners take home a decent packet.

There are little in-jokes – returning categories like "Pot Pourri" and "Oh No It's Opera", or phrases that rhyme. Trebek never sings, but reads out lyrics in a deadpan. Alex's polylingualism means he's great at accents, and often throws foreign phrases at contestants who mention that they are fluent in another language. Should a contestant mispronounce something, Alex casually corrects them while asking for what's next.

- Alex: It takes 84 earth years for it to go around the sun.

- Player: What is Uranus?

- Alex: Yes, the planet.

Spin-offs over there include primetime championship show Super Jeopardy! (1990), children's version Jep! (1998-2000), Rock & Roll Jeopardy! (1998-2001), and Sports Jeopardy! (2014-16).

They've tried three times to make Jeopardy! a hit over here. Derek Hobson hosted a series on Channel 4 in 1983-4, then Chris Donat and Steve Jones (1) fronted ITV series between 1990-3. Paul Ross tried and failed on The Satellite Channel in the mid-90s, during which time they also showed Alex Trebek's version.

At heart, Jeopardy! is a test of general knowledge. Tempered a little by the wagers, and tempered a lot by the buzzer signalling devices. It's an oasis of pure skill and refinement in a television schedule that often favours the lucky, the headstrong, and the boorish. And that, we suggest, is why Jeopardy! hasn't caught on over here.

We have many shows in the same gap. For many viewers Jeopardy! would be just another quiz, one that isn't The Chase or Pointless or Fifteen-to-One. And it would be expensive, Jeopardy! has a massive reputation, and would attract huge licensing fees. We can imagine the BBC staging a tournament during Strictly On Two season (nine weeks of heats, daily winners to Thursday finals, weekly winners come back for Finals Week in December for the huge prize), but would it be more cost-effective to make House of Games (3)?

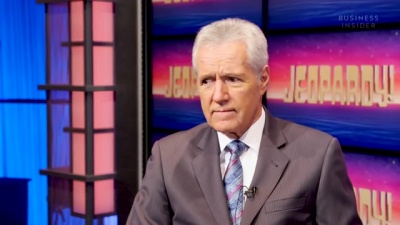

But these are parochial issues. Alex's suave and classy presenting style combined with his formidable knowledge makes him the perfect Jeopardy! host. Put simply, Jeopardy! is Alex Trebek, and Alex Trebek is Jeopardy!.

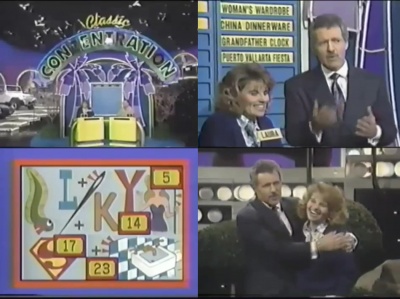

Classic Concentration

But wait, there's more! Alex Trebek appeared on ValueTelevision, a cross between a talk show and a home shopping channel. Heart of Courage, far less nauseating than Esther Rantzen's equivalent. He also hosted Classic Concentration between 1988 and 1991, episodes picked up over here as cheap filler on The Lifestyle Channel.

The show is simple. A board of numbers hides matching prizes, and our players open two doors at a time. Match a pair of items to win them on your side of the board; no match and play goes over to the opponent. Behind the matched numbers is a rebus, one of those puzzles made up out of pictures and letters. Solve the rebus to keep all the prizes. Best of three earns the chance to win a brand new car.

Played absolutely straight, this could be done in about ten minutes. Alex chatters to the contestants, helps them talk about their relations and their aspirations for the prizes. He looks after the administration, reminds players to use their "Take" options, and makes sure the game continues to tick along at a brisk pace.

The main game rewards careful viewing. We need to be watching carefully to play along with the memory aspect, and it's in the player's interest to keep clearing the board. That also makes the rebus easier for people at home, and lets us think "cor, we're so much smarter than them on the telly".

Concentration is an absolute gem of a show, so simple that anyone can play it, and with enough drama to keep attention. Compare this simple and elegant format to The New Battlestars from last week. TVS made a version over here in the late 80s, but the Mark Goodson corporation haven't sold it in donkey's years. Might be worth another look.

To Tell the Truth

A panel game of little consequence. Someone with an interesting story comes to the studio, and tells their story. Two other people come to the studio, and pretend to be that person. The panel's job is to ask questions of the guests, trying to work out which are the imposters and who is sworn to tell the truth. It is a game, anyone who deceives the panel earns $500 per vote, but this is incidental.

Alex Trebek hosted the 1991 revival, full of minor daytime celebrities of the era. His main role was to keep everyone to time, and to read out the statement put forward by the real person. Alex would also talk with the real star, the person with the interesting story to tell, and he'd make sure the interesting story got told.

In a coda to the show, a member of the studio audience is picked to work out which one of two stories is true. They're helped (or hindered) by questions from the celebrity panel. Over here, To Tell The Truth had a couple of series on Channel 4 in the early 1980s; the market for celebrity gabfests has dried up since.

Over the course of a day in 1991, Alex Trebek hosts three very different shows. Jeopardy!, a fast-moving game of answers and questions. Classic Concentration, fun and rebuses and lots of prizes. To Tell The Truth, a people show where stories – true and false – are told. Each shows a different aspect of Alex's versatile skillset; all of the programmes are enhanced by their host.

There is a point when a game show host becomes an institution, and Alex had crossed that mark by 2001: the simple act of shaving off his moustache caused uproar amongst the Jeopardy! fandom. He hosted his 6829th episode of Jeopardy! in June 2014, the most episodes of a single game show hosted by one person, breaking the record previously held by Bob Barker of The Price is Right.

He was nominated for Outstanding Game Show Host almost every year, and won this Daytime Emmy award in 1989, 1990, 2003, 2006, and 2008; a Lifetime Achievement Award was bestowed upon him in 2011. He was also honoured by geography societies, for his off-screen work encouraging students to learn about the world. He has stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and Canada's Walk of Fame, and was presented with the keys to Ottawa City in 2016.

We learned in February that Alex had a serious form of pancreatic cancer, and later that the prognosis was not good. By some miracle, the cancer has responded to treatment and gone into remission. We hope Alex has a long and happy life ahead of him.

BBC Brain

The grand final of Radio 4's Brain programme. Many have come, all have tried, and the final four took their place alongside host Russell Davies on the BBC stage.

An early question asks about Miles Jupp, who stepped down as host of The News Quiz earlier this year. "Best known as Archie The Inventor on Balamory; don't think he was over-extended in that role," snarks the host. Really, Mr. Davies? We know a five-year-old who will fight you on that point.

After two rounds, it's very close, no-one has run away with it. Roger Luck has a one-point lead, but a five-in-a-row will propel anyone into the lead. Or just a guess – Calendar Girls (the Tim Firth – Gary Barlow musical) helps put Frankie Fanko ahead of the pack.

"Murder Ahoy! is the least-known film of Margaret Rutherford as Miss Marple," opines the host; those of us who remember Black Type in Smash Hits might beg to differ. After the break, we have a decisive move: David Stainer scores four in a row, stopped only from the bonus because he didn't remember Acheron the ferryman of the dead.

The decisive moment comes when Frankie zigs with Christine Keeler; the answer is Mandy Rice-Davies, "the other one", a bonus to David. The theme from the recent Captain Marvel film beats the panel, all four offer recent superheroes. Going into the final round, David's lead is three points.

Frankie gets a bonus, but only one on her own run. Roger could still have won, but required overthrows, and calls it a day on two. The bonus goes to David Stainer, and that wraps up the match; confusion between Edie Brickell and Suzanne Vega ends the contest on a high note.

The final results: Gareth Aubrey 4, Roger Luck 11, Frankie Fanko 14, the winner is David Stainer on 16 points. In a brief speech, David notes that it's the third final he's been in, and invites all of the others to make another go of it.

BBC Brain returns in about 35 weeks. Set your calendars!

This Week and Next

Thanks to Daniel Peake for research assistance this week.

Attention: fans of the same thing happening every few seconds for hours on end! We have a show for you! Cannonball has been bought up by NBC. Fun to look at, tempting to do, but after you've seen one episode, you've seen them all (as we said in 2017). It'll pair well with their coverage of the N"F"L.

BARB ratings in the week to 7 July.

- A new leader on television: The World Cup with Gaby Logan: The Football Association XI -v- United States Football Federation XI (BBC1, Tue, 9m). Expect a series. Top game show was Love Island (ITV2, Wed, 6.15m).

- ITV holds down the next five titles on the game show charts, with The Voice Kids (Sat, 3.4m), Stephen Mulhern's Catchphrase (Sat, 2.85m), The Chase (Mon, 2.8m), Tipping Point Lucky Stars (Sun, 2.75m), and Harry Hill's Alien Fun Capsule (Sat, 1.85m). Beneath that: Love Island Aftersun (Sun, 1.82m) and Unseen Bits (Sat, 1.78m).

- The biggest game on BBC1 was Room 101 (Mon, 1.57m); the biggest on BBC2 was Dragons' Den (Sun, 1.23m). This is what happens when they schedule so much sport.

- Good ratings continue for Taskmaster (Dave, Wed, 1.11m), The Crystal Maze brought 1.03m (C4, Fri).

- Two strong launches: The Great Gardening Challenge (C5, Tue, 985,000) and Kirstie's Celebrity Craft Masters (C4, Mon, 705,000).

- Hey Tracey (Mon, 650,000) and Celebability (Wed, 600,000) continue to pull in viewers on ITV2 after Love Island.

Just the one new show of note: The 3rd Degree (Radio 4, Monday), a challenge for university students and their lecturers.

Photo credits: Merv Griffin Enterprises / Kingworld, WGBH, Business Insider, Mark Goodson Productions.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.