Weaver's Week 2020-04-12

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

This week, ITV will show Quiz, the television drama of a play based around the Ingrams' cheating scandal on Who Wants to be a Millionaire. We've covered the case in great detail – a contemporary report of the trial, a recap five years later, and a review of Bob Woffinden and James Plaskett's book "Bad Show".

One of the lines used by the Ingrams and their defenders was that they tried to be smarter than the producers. There are many examples of people working to beat the game. For shows like Countdown, it's sheer practice; even on The Krypton Factor, one can train for some of the rounds.

Sometimes, the way to beat the game is to exploit weak design. On Raise the Roof, the second round would drop the one contender of three with the lowest score, and anyone who didn't give a correct answer would lose the points they'd bet. A very small wager would ensure a player couldn't lose, and it was all entirely within the rules.

Back in 1984, viewers to CBS saw the most obvious example of a game show player being smarter than the producers. No whammies. Just big bucks.

When Press Your Luck Got Hacked

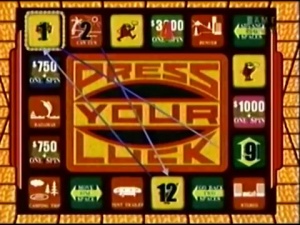

Press Your Luck was a half-hour daytime show, played by three contestants. It went out on the CBS network, usually at 4pm, from September 1983. A short series of trivia questions allowed the players to earn "spins" on the show's main attraction, the "big board".

The "big board" was 18 squares, arranged around the edge of a 6x5 rectangle. Each square on the board cycled between three images, and a flashing light illuminated one of the squares, moving more quickly than the cycle of the images. It's a bright, always-changing, almost hypnotic display.

When the player pushes their button, the mechanism stops. The squares keep their images, the light stops moving. Whatever is showing in the square takes effect. Most often, it's cash; sometimes a prize, occasionally a choice of other squares on the board. Hit one of those and the player adds that money to their personal bank.

But sometimes the square contains a diablo, a little devil, a "Whammy". Hit one of these critters and everything in your bank – cash, prizes, the works – is lost. Hit four Whammies across the whole show and the player is eliminated from the game.

Press Your Luck had debuted in September 1983, just one of a dozen or so game shows syndicated across daytime television. It lasted three years on the CBS network, and has had a couple of short-lived revivals. Over here, some episodes were shown in the early 1990s on the Lifestyle and Sky One blocks of "The Great American Game Shows"; HTV had its own short-lived version hosted by Paul Coia. But for this one event, Press Your Luck would be unknown over here, and probably as dimly-remembered as Body Language in its homeland.

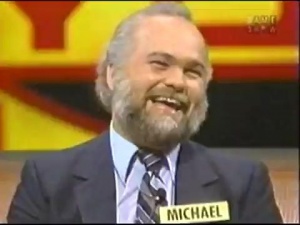

In Ohio, Michael Larson was a bit of an oddball. He didn't hold a steady job, describing himself as an "ice-cream truck driver", Michael did have a lot of television sets and video recorders at home. He was convinced that sooner or later, someone would make a big-money game show with a flaw in it, one that he could exploit and earn a fortune. Press Your Luck had that flaw.

Although the squares on the big board appeared to light up at random, this was an illusion. The board actually moved in one of just five patterns. The producers were aware of this, it's a limitation of the computer power available in 1983. Random number generators are expensive and complex to program, and easy to go wrong. It's far easier to cycle between the various squares in an apparently random pattern. Surely no-one's going to spot this, not unless they programmed the whole system... or they've got far too much time on their hands.

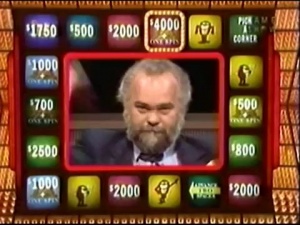

We join the recording on 19 May 1984, for the show to be transmitted on 6 June 1984. Defending champion Ed Long is joined by Michael Larson and Janie Litras. "He feels creepy" thought Janie, "and I look forward to beating him."

The host, Peter Tomarken, starts the show by publicising the home viewer sweepstake. One of the spins early in the second round would be the Home Player Spin, and a viewer's postcard would be pulled out to win what the studio player won – up to $5000 cash, and a guaranteed minimum of $500.

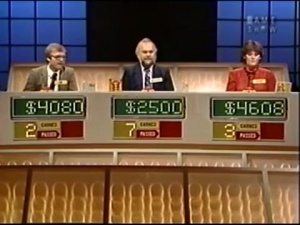

After the opening round of questions, Janie has a massive 10 spins on the board, Ed has 4, and Michael 3. The player with the fewest spins goes first, and that's Michael. And, perhaps because he's not yet warmed up, perhaps because he doesn't know the buzzers are super-responsive, he hits a Whammy on the first attempt. On the other two spins, he hits one of the board's biggest prizes, $1250 twice. Ed takes his bank to $2980 before running out of spins, and Janie reaches $4608 before passing two spins to Ed. He has to play them, and finishes on $4080.

All of this is entirely hypothetical, of course: the prizes are surely not going to be awarded. Whammies will wipe out this money, and it'll just be random chance, the winner will be decided by who doesn't hit a Whammy late on. That is what always happens on Press Your Luck.

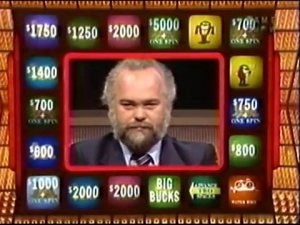

Round two begins with the trivia section: Michael takes 7 spins, Janie 3, and Ed just 2. Peter reminds us that the Home Player Spin will be decided soon, and the player with the lowest score starts the game. That's 7-spin Michael Larson.

$4000 and another spin, the top prize on the board. That's the third time in a row he's hit the top prize, and that's desperately unlikely – about one chance in 5000. But across the series, there will be something like 6000 series of three spins, and this has to happen sooner or later.

$5000 and another spin. "You are on a roll, Michael." He goes off to the side – picking up $1000 and a spin, then a trip to Hawa'ii.

And then it's back to the jackpot squares. Michael continues to press his luck, and reaches the Home Player Spin. It's a viewer called Michael from Louisiana: he wins $1000, Michael Larson wins $1000 and keeps his spin. He's now passed $20,000, surely the point where anyone wants to stop.

Michael presses on. Back to the side for another $750, and then to the top for $5000. Pick A Corner earns $2250, there's a sailboat.

And throughout, Michael is a picture of concentration. He takes his time, he's not rushed into pressing the button quickly, lets it roll until he feels lucky. Sometimes five seconds, sometimes a full ten seconds.

Another production decision came back to haunt them. Some of the squares on the board would never contain a Whammy. The biggest prize – the "big bucks" of the chant – was always in the same square, fourth along from the top left corner. In the second round, where the largest money was to be made, these "big bucks" always gave an extra spin, prolonging your game. If you could be sure of always landing on that square, or the Whammy-free one in the middle of the right edge, you could prolong your game almost indefinitely.

...and so long as you don't make a mistake. One error could wipe out the entire bank. One split-second change in your reaction time, and boom! Twenty thousand is lost, gone, up in smoke.

Michael is prepared to take that gamble. He presses on. Past $30 grand. Past $40 grand. "Oh my! Oh my! Over 40 thousand on one spin. This is unbelievable! Never seen anything like it!" Peter Tomarken is exhausting his vocabulary. The crowd is cheering as though they're witness to one of the greatest spectacles in television history. And the crowd is right, they are witness to one of the greatest spectacles in television history. Michael takes a moment to compose himself, and carries on past $50,000. Past $60,000.

"You have over sixty five thousand dollars!" shouts Peter. "Do you know what that means?" Michael shakes his head. No. No, he doesn't know what it means. It's numbers on a screen, it's a life-changing amount of money. For an unskilled worker like Michael, $15,000 was a reasonable annual take-home pay in 1984. This one show represents four, five, six years of driving his ice cream truck around Ohio.

And still Michael plays on. It's a physical effort, intense concentration and presence of mind. The crowd is baying. Peter is hollering. The contestants on each side are clapping. He's going again, again, again. Up in the gallery, the production staff are concerned – it's clear that Michael is on to something, but they're not sure what. They'll have to ride it out, figure it out later.

Eventually, to everyone's relief, Michael stops. $102,851 in 1984 dollars. Something like seven year's income. His four spins go to Janie Litras, the player in second place at the moment. But defending champion Ed Long is first to go, with two spins of his own. On his first: it's a Whammy. Only the second we've seen today.

Ed plays catch-up well, twice hitting $5000 and a spin, before hitting another Whammy. His grand non-total, zero dollars.

Janie hits a Whammy of her own, so she's now got 6 spins to play with. She plays on for a little while, and takes her total to $9385. And then she passes three spins to Michael. What's his exit strategy? How does he escape from this paradise of his own making?

Ah. Michael had memorised the two important patterns, he could land on always-safe squares 4 or 9 at will. But had he committed any other patterns to memory? Squares 2, 10, and 13 were also free of Whammies, but did he know this? Perhaps he didn't, perhaps he didn't care. He played out the three spins he'd been passed by Janie. His winnings go up to $110,237.

On the last of the passed spins, Michael makes a slight mistake, he stops the board a beat early, and lands on the square before 8 in the sequence. He's just missed $700 and a spin, and earns a trip to the Bahamas. The third item in that square was a Whammy. Had the board been in a slightly different configuration, Michael would have gone down in history as the man who just lost more money than anyone on any game show ever.

To close the show, Janie takes the two mandatory spins, wins cash and a prize, and that is the game. All of the spins have been dealt with. Ed leaves with the winnings from the last episode, Janie with her place in history, and Michael escapes with over seven year's wages. He plans to buy a house with his winnings, and "a surprise" to her daughter on her birthday.

As we've noted, the producers were clearly aware that something was badly wrong. The prize budget was a line item on Press Your Luck, somewhere between $5000 and $10,000 per episode. Michael's just snaffled a month's worth of winnings in one day. But there was nothing they could do – Michael had exploited a weakness in the game, and had to be paid. He'd put in the hours, done the homework, and earned a rich reward.

CBS were mightily unhappy about this, of course. The mega-corporation had been played, and had been badly beaten. After some internal muttering, they did show the game – spread across two days, because it was far too long for a one-day match – and hoped that would be the end of it. The gameboard was changed to include lots more sequences, and reprogrammed over the summer so that there were no safe squares. The Michael Larson episodes weren't included in syndication packages, and weren't broadcast again until the Game Show Network made a documentary about the events in 2002.

Michael Larson's life did not have a happy conclusion. Hoping to hit the jackpot in a radio station promotion, Larson withdrew about $50,000 in one-dollar bills – the cash was later stolen from his home. There was a lottery scam, and ultimately Michael died of throat cancer in 1999, at the age of 49. His record of the biggest one-day win on a daytime game show was eclipsed by 2005, when Jennifer Miller scooped £120,000 (then about $206,500) on our Deal or No Deal.

In other news...

Troubled days at Channel 4. The publisher-broadcaster is to reduce its content budget by £150 million, about 25% of its entire expenditure. With no studio arm, Channel 4 is at the mercy of the advertising industry, which has completely collapsed in the last few weeks. Junior Bake Off is off, at least for this year. It looks like the entertainment channel E4 will be badly hit, and there may be fewer commissions on More4. Not good news for fans of Jon Snow's Very Hard Questions, then.

A new idea on the Beeb this week, Pointless Chain Letters. Take a common word, like "LINE". Change one letter in it to form a new word. Work out how many of the Pointless Hundred gave those answers, to find out what the word's worth.

The death of Honor Blackman, best known as Cathy Gale on The Avengers, and in these parts as the fruity voice on Chris Tarrant's short-lived Lose a Million.

ITV's big drama for Easter week is Quiz (Mon-Wed), telling the story of the coughing scandal on Millionaire. The new version is back, with a Who Wants to be a Millionaire Celebrity Special (ITV and VM1, Sun).

On BBC2, I'll Get This returns (Tue). Angela Barnes takes over on The News Quiz (Radio 4, Fri), and it's the grand final of Masterchef (BBC1, Fri).

Photo credits: Celador, CBS / GSN, EBU / ÖRF.