Weaver's Week 2014-02-02

Last Week | Weaver's Week Index | Next Week

"A revolution in quality and choice."

Contents |

23¾ Years of KYTV

What you're about to read is a spoof. A satire. There are elements of truth, there are elements of fiction, and we don't much care for the dividing line.

Ahead of its scheduled launch in February 1989, KYTV talked a lot about how satellite broadcasting would bring about a revolution in the way we saw television. We were promised a revolution in quality, and a revolution in choice. Over the next two weeks, the Week will look back over the course of these revolutions, and review a few of the game shows that were a part of that time.

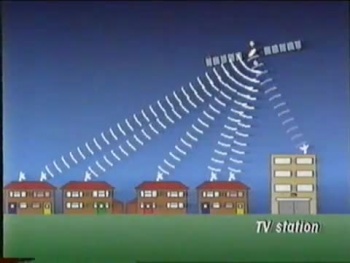

Satellite television didn't begin at the start of 1989. It has a longer history, stretching back to the launch of Telstar in 1962. By the late 1960s, it was possible to send satellites to a height of 23,300 miles. At this magic altitude, the satellite orbited the earth once per day, so it appeared to stay in the same place in the sky. Broadcasters and receivers could point their dish at a certain point, and leave it there, and it would always work.

At the start, Direct Broadcasting by Satellite (or DBS as it was known at the time) was only available to professional broadcasters. As the 1970s progressed, the price came down, and by the time the government of Mrs. Thatcher took office, private citizens began to afford their own satellite dish. The government commissioned an inquiry in 1981, and it decided that the UK should have her own satellite broadcasting system.

Rather than rent space on a pan-European satellite, as The Satellite Channel and Superchannel had done, the UK government decreed that there would be a British satellite for British programmes. The DBS committee also decreed that this British satellite should be at the cutting edge of technology, and use the new MAC broadcasting format. The European Community and technical advisers were in favour of this standard, but the BBC preferred to start with the existing PAL format. We'll come back to this format war a little later.

When this decision was made, in late 1982, the proposed launch of DBS was in 1986. It didn't happen. Not until April 1986 did the Independent Broadcasting Authority invite bids for the UK's three DBS channels, with another two reserved for the BBC. Five consortia entered bids, offering three of an entertainment channel, a news channel, a sport channel, a film channel, and a family or children's channel. BSB UK (supported by Carlton and LWT) would have brought in the Super Channel that brought Going for Gold to the continent. The National Broadcasting Service and SatUK would have had pay-television. Direct Broadcasting Limited involved the News Transglobal corporation and would have included The Satellite Channel.

The winner was British Satellite Entertainment, a consortium involving Granada and Anglia, Pearson, Virgin Group, Amstad, and ITN. Their offer was four channels in three slots: children's channel Zigzag and a pay-movie channel shared time, Galaxy was to be entertainment, and Now intended to be news and features. Shortly after winning the contract, Amstad withdrew from the consortium. BSE hoped to cut the price of a satellite dish from £1400 to £250, and Alun Salty now thought this was impossible.

While game show analysts untangled that mixed catchphrase, Alun Salty did the hokey-cokey. Having been in, then declared himself out, he went back in with a new partner. Sir Kenneth Yellowhammer and the News Transglobal company had bought The Satellite Channel, renamed it after himself, and prepared to market it to Britain. Amstad suddenly found itself able to produce DBS receiver dishes for under £250, completely contradicting the bold claims of its chairman Alun Salty a couple of years earlier.

At 6pm on Sunday 5 February 1989, the unofficial, unlicensed DBS network began broadcasting. The first programme was "The Revolution", a thirty-minute puff piece hosted by Mike Flex and Kay Burley, expounding the bold new world of satellite telly. Movies you've never seen before! All the top sporting action on Europa Sports! News when you want it from a team of top reporters and Kay Burley! Celebrity interviews with Mike Flex, the man they're all talking about! And all the best in entertainment!

The reality was somewhat different. Live log-chopping from a muddy field in Austria was the centrepiece of Europa Sports' schedule, while Frank Bough's long discussions on the news station concealed a lack of footage of the year's big stories – the demolition of the Berlin Wall was demonstrated by a Lego construction. Movies such as "Middle Gun" and "Days Of Distant Rumbling" had never been seen before, or since. But there were new, original, and innovative game shows. Like

Sale of the Century

Reg Grundig Productions (GB) for Kenneth Yellowhammer Television, 1989-91

"See Edna battle for a lawnmower!"

With an opening announcement like that, there's only one thing we can possibly do. But we'll remember our motto – we watch these shows because someone has to – and take the batteries out of our remote control.

The basic concept of Sale of the Century is that a quizmaster reads out general knowledge questions, contestants compete to answer them on the buzzer. Five quid is added for a right answer, five quid deducted for a wrong one. Every so often, the questions stop, and there's an instant sale: some item of household goods is offered at about 10% of its retail price. The first player to buzz in and take the deal wins the prize, but has some money deducted from their total.

At least, that's how they played it on ITV. The version on the satellite had one crucial difference: only the leader was allowed to buzz in on these instant sales. Players might like to buy a two-band cassette-stereo clock radio (usually £56) for £6, from Sale of the Century and Pennysonic. But unless they're in the lead, they're not going to get the chance. This is a clever tactic by the programme makers: rather than pay out for some moderately expensive prizes, they can give the contestants the deflated cash equivalent. The leader not buying the radio has saved the producers £50. With four instant sales per show – most offering more valuable items – and only one bought, that's £200 off the episode's budget already.

This edition was hosted by Peter Marshall, an urbane announcer who had worked for Thames and Anglia. He was born in Derry, so had an Irish lilt to his voice. A round on this show brought to mind another Irish quizmaster, as "The Fame Game" was a long question of the form "Who am I?" Contestants could buzz in at any time, and a correct answer was worth four points – no, it was worth a pick from the Star Board, nine squares hiding various little prizes worth up to a hundred quid, or some money for the scoreboard.

At the end of the game, there's a one-minute speed round, a genuinely tense finish. There are parting gifts for all players, the Yellowhammer Press Atlas of the World; the rest of us could buy it for £15 from Sofa Shop ("you spend, we send"). The champion had the option to use their winnings in the main prize sale: a washing machine reduced from £289 to £80 from Sale of the Century and Zamussi. Or the winner could come back on the next show, and trade up to a better prize. A trip to Brazil for £480, or the top prize of a car which would cost £585.

The result? Most winners will come back, most winners will be defeated before buying anything expensive, and most of these big prizes don't get won. In a sample show we've seen, the only prizes dished out were a teaset, a children's pinball game, those two atlases, and £125 in cash. Might be a prize budget of £300, though £1500 of goods had been on offer. And the show looked like it had been made on a restricted budget: the graphics were plain, the set decoration simple, there was liberal use of pre-recorded inserts to promote the larger prizes. And it had clearly been made on the Going for Gold principle of recording a week's worth of episodes in a day.

"When it comes to quality, we stop at nothing," declaimed Mike Flex in the opening transmission. This was confirmed by the programming: very high expectations were undermined by very modest shows, a problem that only worsened as the company developed and budgets were trimmed. Another problem was that no-one could actually watch these channels. Though Amstad had said they could make a satellite dish for £250, and indeed did make a satellite dish for £250, the company was only able to make a few dishes each day. Most of those were given away to readers of Sir Kenneth Yellowhammer's papers, and only a few were sold. Not until late 1989 would Amstad be able to keep up with demand, and those oh-so-discreet dishes began popping up around the country.

KYTV had pledged to make 20 hours of entertaining British television each week, and they certainly made 20 hours of British television each week. Five of those hours were a late-night talk show hosted by Derek Jamieson. The show was a bit like the BBC's more successful Wogan, but with guests who wouldn't be let into Television Centre unless they bought their own mop and bucket.

There was the new Love at First Sight, a show that inspired the most-seen page on the UKGameshows website and wasn't a knock-off of Blind Date at all. There was Mike Says Here's a Bit of Talent, an innovative programme that owed absolutely nothing to Bob Monkhouse or Hughie Green. And there was a trip to Nottingham for a programme completely unfamiliar to audiences who had never seen anything like it on their screens before:

The New Price Is Right

A Talbot Tellygame for Kenneth Yellowhammer Television, 1989-90

Same studio as on the ITV version, check. Same hyped-up audience as on the ITV version, check. Same dècor as on the ITV version, check. Same format, same structure, same games. Most of the points from our review last April apply to this version, too.

There were a few points of difference from the familiar programme. Leslie Crowther had been too much of a name, or too expensive, and had been replaced by Bob Warman. Bob was (and still is) a newsreader on Central Television, and didn't have to travel far to Central's Nottingham studios, seeing as how his day job was at Central's studios in Nottingham. The theme tune was slightly different, and we think the logo had changed. Certainly we don't recall the guesses on Contestants' Row being displayed in coloured lights.

Another point was that the prizes had reduced in value somewhat. In 1984, the typical Contestants' Row prize was valued at £125. In 1989, it was nearer £90; accounting for economic change, a 35% prize deflation over five years. The "Ten Chances" game was one of the cheapest main prize games under Crowther; for Warman, it offered the night's biggest prize.

At this time, Kenneth Yellowhammer Television operated under a permit issued by the ever-so-accommodating regulators in Luxembourg, and broadcast using the Astral satellite owned by Luxembourg company SSE. A similar arrangement had enabled Radio Luxembourg to bring commercial radio to the UK three decades earlier. In particular, Luxembourg had different rules on ad breaks, show sponsorship, and the placement of logos.

These differences were going to be exploited to the full. The New Price is Right was able to have three commercial breaks in the middle of the programme, an equivalent on ITV would only be allowed to stop for adverts once. The IBA had "suggested" that Central discontinue the whirly wheel; the satellite version brought it back. The makers of the prizes were named in the commentary, and displayed on screen, something the British regulator would never allow.

The Price Is Right is a difficult show to get wrong; all you need is a hyped-up crowd and some prizes, and it'll look OK. It's a fiendishly difficult show to get right, and we found this version to be a little too cheap and a little too tacky to be better than OK.

In its original publicity, KYTV had promised us two further channels before the end of 1989. The Mouse Channel would be programming for the young and the young-at-heart, but this didn't launch until 1995. KYTV Arts was even longer in gestation: also scheduled for a 1989 launch, this channel didn't appear until 2007, five years after the BBC equivalent, and then only after KYTV had bought out a rival broadcaster.

Running late would be the lasting legacy of the other satellite company, British Satellite Entertainment. They began a massive publicity campaign in April 1989, ahead of their planned launch in September of that year. The massive publicity campaign ground to a halt in May 1989, when it emerged that the company wasn't actually going to be ready to start broadcasting in September, and had confused "the launch of the channels" with "the launch of the rocket that's going to broadcast the channels". They also wanted to source a stock of the small and attractive Squarials, learning from KYTV's mistake.

As we noted earlier, British Satellite Entertainment was using a different transmission system, called D2MAC. The analogue television signals used at the time were made up of data for brightness and colours. PAL, the system used by the BBC, IBA, and KYTV, gave brightness and colour data at different frequencies, all at the same time. D-MAC gave this brightness and colour data at different times; it also had higher-quality sound. D2MAC was a slightly compressed version of this standard.

The net result was that British Satellite Entertainment would give much higher quality video, and could be received on much smaller dishes, so long as the entire broadcast chain (from Marcopolo House to receiver) used D2MAC. There was a clear difference between the sharpness and clarity of these quality analogue broadcasts and the muddy mess of PAL. The comparison was made clearer by a fault on the Astral satellite, which led to little specks appearing on the picture. None of these "sparklies" on the other side.

British Satellite Entertainment made some arty black-and-white adverts, suddenly springing into colour when one of their five channels appeared. BSETV promoted itself as "five-channel entertainment"; dedicated films and sports channels, a current affairs station Now, music on The Power Station station, and the general entertainment Galaxy station. The broadcaster promoted itself to the trade via a 30-minute promotional video featuring one of its most recognisable signings, Mike Smith.

Another signing on the network was Broadsword, with an out-of-this-world fantasy adventure show.

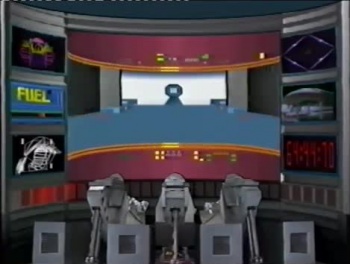

The Satellite Game

Broadsword for Galaxy, 1990

From the opening moments, it's clear that this programme is Knightmare for a different audience. An epic opening sequence is followed by an introduction from the notional host. There's a team of three young advisers, eager to help their charge succeed on a fantastic quest. It's on a satellite from out of this sector, with the potential to blow up and destroy life as we know it.

The biggest problem we had with Knightmare was how the fourth member of the team had to be blindfolded, so they couldn't see the projection screen. The Satellite Game solved this problem in a most elegant manner: the team's representative isn't a fourth human, but a robot droid, LARI. While this got round the big conundrum, The Satellite Game introduced many new ones.

The minor problem we have is of appearance. On Knightmare, contestants would be leaning forward over a viewing screen, looking eager to progress the game. On The Satellite Game, they're strapped in to couches, watching the action on an overhead monitor. From most angles it looks like they're lying down, it looks like they're ready to fall asleep.

Also, the whole show is shot using computer graphics. By 1990, there was enough computing power for graphics to animate in real time, so long as the animations aren't very difficult. In practice, that means lots of chasing LARI up a featureless corridor, or keeping him still while other action plays around him. Moore's Law meant that computer animation would improve tremendously during the next few years, and Broadsword may only have been a little ahead of the technology.

The most significant problem is that there's so little for the youngsters to do. They're not the protagonists of this adventure, they're not the antagonists, they're not the advisers. For far too much of the programme, the team is the audience, sitting through bickering between the ship's computer and the remote-controlled probe. As an occasional aside, this humour is invaluable; when it becomes the main aspect of the programme, it becomes insufferable. In the first 20 minutes, they meet precisely two alien droids (evil), encounter one alien (camp), and have no way to win or lose.

This is a shame, because there was a sniff of a quality programme in there. The closing moments saw the players take direct control of LARI through joysticks, and there's a logical plot reason (his computers are damaged and need repair). Witty commentary from David Learner as LARI – an exasperated aside of "oh, squarials" raised a laugh at this distance. And we're intrigued by the credit to one Alice Arnold in the cast: is this an early appearance by the future Only Connect team captain? Was the whole programme a very subtle allegory about the dangers posed by unlicensed transmissions, and discouraging people from looking at the other orbit? We may never know.

When the DBS contract was awarded in 1986, people told the news that it would take 10 years for the DBS contract to become a serious moneyspinner. British Satellite Entertainment had finally launched in April 1990, so it would be the turn of the century before it started to make money. Ten years of selling satellite dishes. Ten years of exclaiming, "oh, squarials!". Ten years of promising high quality programmes, ten years of the programmes being not quite as good as that. And, most importantly, ten years of selling advertising and flogging subscriptions.

Ten years? Give it twenty-seven weeks. The costs were mounting. The revenue was flat and falling, and there were worries about a looming recession. Most crucially, the premium programming was split: both KYTV and BSETV had adequate but not brilliant movie packages, and between them they had a credible sports line-up. At the start of November 1990, a proposal was put to the prime minister. It sought an equal merger of BSETV and KYTV, otherwise one or both might be out of business by the end of the month.

What will the prime minister say? Will she take the subtle propaganda of The Satellite Game, or will she chase the support of Sir Kenneth Yellowhammer's large-circulation newspapers? Who will keep their job? Who will be taken off screen? We'll tell you next week, as our whistle-stop tour of Direct Broadcasting by Satellite concludes.

University Challenge

Group Phase 1, Match C: Somerville Oxford v Clare Cambridge

York and Pembroke Cambridge fell to Somerville Oxford; it may be a coincidence that Pembroke were sat in these seats a year ago. Clare put an end to Loughborough and drew with Christ Church Oxford in their earlier matches. Somerville play their reserve this week, Sam Walker enters at seat one replacing Hasheen Karbalai.

Clare got off to the better start, picking a full set on a Dutch city, and doing well on eponymous charities and physics acronyms made from girls' names. Somerville pulled back with questions on inequality metrics, but Clare scored on places named in literary fiction, and led 80-20 after that visual round. Clare pulled further ahead, slipping up only on pioneer climatologists, suggesting one of them was "Jeremi Paxman". Wasn't he a notorious beard?

Going a hundred points down seems to have brought Somerville back to life, picking up a couple of starters and recognising the drone of Laura Marling and other habitues of the Cambridge Folk Festival. They recognise the Proclaimers but not Hayseed Dixie, thus proving that it's no disadvantage to look like our founder. Which brings us to a bonus round on German board games, on which the Oxford graduates achieve perfection.

Astronomy and taxonomy combine for a round on celestial insects, giving Clare a few more points, but Somerville pull back thanks to knowledge of the German city-states. The second visual round is a Golden Hour classic: name that year from photographs of G7 leaders and nothing more. Neither side gets the starter, so Clare's lead is now trimmed to 135-120. But Clare are very impressive by naming all three years in the bonus section. Somerville are on a roll, getting the next two starters and pulling out their first lead of the night.

Game on! Two minutes to play, and Somerville scores the next starter, extending their lead to 15 while chewing up the clock as much as is humanly possible. The game is won when Somerville come up with Dutch place names beginning with an apostrophe, and the gong goes before the next starter can be answered. Somerville's winning score is 195-160. Strong bonus performances by both sides: 16/24 from Clare, 19/30 from Somerville.

University Challenge hasn't formally published the next match since the end of the first round proper. By process of elimination, it must be Southampton and Queen's Belfast next week.

This Week and Next

We're pleased to hear that Big Star's Little Star has been picked up for further episodes. Not just because 12 Yard has finally got a programme renewed on ITV, but because it was an entirely lovely hour of television, like relaxing in a warm bubble bath. Not a description we can use of Release the Hounds, picked up for a six-episode run. Well, six episodes of running.

From the blue wire, we read Louis Virtel's six lessons from winning $38,000 on The Chase. He gives a lot of time to the star of the show.

And so to somewhere slightly less exotic, Salford, for Mastermind.

- Richard Pyne (History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew) gets a potted history of the subject, in which plants the seeds of a successful round, and digs up a few good answers to finish on 11 (1). And that put him last! The contender could go from fourth-to-first, but rather shot his bolt with a number of passes in the opening stages. He answered everything quickly, and finished on 25 (5). That's a decent target.

- Ben Holmes (Manic Street Preachers) The round on the South Wales neo-punk rockers began with a pass, but recovered very well, finishing on 12 (2). His general knowledge round never seems to get out of third gear, but it turns out to be very effective. 26 (4) gives him the lead, and sets an even more decent target.

- Alister Jones (Edmund Hillary) Everyone knows about the subject's mountain-climbing exploits, it's less well known that he crossed Antarctica back in the days when this was a remarkable feat. Speaking of which: 13 (0). Another slow start, with quite a few passes, and some credible but incorrect guesses – Mr. Pyne's credible guesses had mostly been right. The contender finishes on 24 (3).

- Sarah Greenan (Ghost stories of M R James) has a round of questions on ghost stories by someone we hadn't heard of until the round began, and about the only thing we learn is that James was active in the 1920s. The barrister has learned more, finishing on 13 (0). There was no slow start to this round, the contender had a large task to do, and chipped away until it was complete. One question plugged BBC Radio's long-running documentary The Archers, another was a plot line from ITV's Mr Selfridge. "Chipped away until it was complete?" 25 (5).

Which means that Ben Holmes has the last word tonight, he'll be progressing to the second phase. Across the show tonight, we've had 100 correct answers, and any of these players could have won in many other heats.

Five from the BARB ratings for the week to 19 January.

- BBC The Voice of Holland of UK scored 8.9m in its second week, ahead of the top Coronation Street episode (8.5m).

- Dancing on Ice (5.4m) only just beat Who Dares Wins (5.2m) and BBC2's The Great Sport Relief Bake Off (5.05m).

- Splash! (3.45m) is only slightly more popular than University Challenge (3.25m).

- Honours even between C4 and C5. Celebrity Big Brother (2.85m) remains ahead of 8 Out of 10 Cats Does Countdown (2.3m), but The Taste (1.15m) is still beating Bit on the Side (1m).

- India's Got Talent airs on Asian channel Colors of a Saturday night, and has 56,000 viewers.

In a quiet week for new shows, we have the new series of Dilemma (Radio 4, 6.30 Tue), a return for Monumental (BBC1 Northern Ireland, 10.35 Fri), and Duck Quacks Don't Echo (The Satellite Channel, 10pm Fri). Raise a glass on Tuesday, it's the last competitive edition of Who Wants to be a Millionaire (ITV, 8pm). Next Saturday's highlight is another chance to see Janice Long on the pilot of 3-2-1 (The Challenge Channel, 7.15); only 35 years later did it emerge that she and Mr. Long had been tipped off about the speedboat by Emlyn Hughes.

KYTV is an original idea by Geoffrey Perkins and Angus Deayton, with pictures from the BBC series of 1990; other pictures from British Satellite Broadcasting, ITN via Transdiffusion, John de Mol Produkties, Reg Grundy Productions, Sky, and Talbot Telegame.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.