Weaver's Week 2016-06-19

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Well, this is awkward. We had hoped to put forward a satire piece loosely based on a joyless Britain after it tried to leave Europe. But fanfic is hard, reality is joyless, and the work we've got isn't anywhere near good enough. This column does at least try to be better than My Immortal, and in this effort we're not.

So, pull out the Emergency Pile of Fun Things From the Internet We Can Watch and Review in One Week.

Game On!

The Internet, 25 February – 31 March

Tom Scott Of The Internet hosts the series. It's a run of six episodes, each contains a game of skill and logic. Tom's co-host is David Bodycombe, games designer. We've not seen any of these episodes before, and we're pausing them to make notes as we go along. And if you want to watch them, each title links to the episode.

The series format is simple. Four players, six episodes. Two wins means you're in the final, two losses means you're on the train home. The final is a one-off match. We're assured at least one repeat match somewhere.

Who plays? A games designer, a video gamer, a mathematician, and a magician.

What are they playing? Games. Novel games from familiar lines: we begin with a round of Rock Paper Scissors Hammer Helmet.

Take, if you will, the traditional pastime of Rock Paper Scissors. Scissors cut paper, paper wraps rock, rock blunts scissors. Win a round and you're entitled to hit the other player over the head with Tom Scott's Massive Mallet. Lose a round and you're allowed to defend yourself with the George Osbourne Memorial Hard Hat. It's a large and awkward shape, and so is the hard hat.

And in the time it's taken us to describe the game, the players are already halfway through. This is Tom Scott's forte: the episodes are short. Really short. None of them lasts more than seven minutes, and we can watch the whole series in an evening.

It eventually becomes apparent that the key isn't reaction times. It isn't winning a game of Rock Paper Scissors. No, the key to this is working out whether you've won or lost, and making the association with the correct object. Or it would be if this wasn't played by a magician, who can win six decisions on the bounce and make the game very one-sided.

Game two was for the mathematician and the games designer. Tumblin' Dice sees dice being thrown down a small flight of wooden steps. Each step has a different multiplier, and the score is what's on the die multiplied by the step it's on. Four dice in each round, thrown alternately.

Special difficulties. It's possible to knock a die out of play and for it to score nothing; it's also possible for dice to pick up a minus score if they don't descend any steps. Is there a tactic to try and knock opponent's dice out, or just to try and accumulate a good score yourself?

Turns out that this is another one-sided contest. The games designer may have rolled dice a lot, and seems able to control them into the Little Four Zone. With her first roll, she picks up a maximum score of 24, and the mathematician can only try and target the opponent's cube.

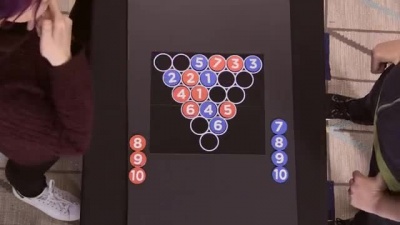

Black Hole was the Elimination match, a test of logic. On a triangle grid of length six, there are 21 spots. Each player has counters numbered 1 to 10, and place them in that order. After they've all placed their counters, there will be one space left: the black hole of the title.

The result is decided by the numbers surrounding the black hole: whoever's total is lower will be the winner, and will remain in the contest.

It means that whoever is going last will have a choice of positions, and will take their best result. So whoever's playing first has to leave a winning position regardless. But the other player knows this, and will want to place accordingly. It's a game of perfect information. There are only a finite number of possible games – 21 x 20 x 19 and so on.

Yes, there's only a finite number of possible games, approximately 51 million million million of 'em. We expect that an interested programmer could work on this problem, assisted by a suitably bored or powerful computer, and crunch through every possibility in a weekend. (Readers: consider this a challenge.)

Is mirroring a good strategy? Is "winging it" a strategy at all? Surely low numbers in the middle, medium numbers around the edges, with the biggest numbers to fill in the holes. Is it a winning move to leave the last two spaces connected, so the last player's 10 has to count towards their score?

On this insight, Red should have the game wrapped up – there are eight spaces, a cluster of four and two pairs. Even with perfect play, Blue will be left with a connected pair, costing 10 points and the game. In the event, play was a little more ragged, but Red still won.

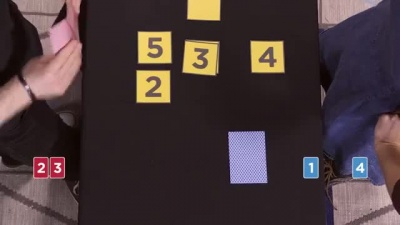

The Semi-Final was Weighted War, "a psychological game of bidding". Each player has vote cards worth 1 to 11 points. The players use these to bid for the score cards, which are offered one at a time. The higher vote wins, and players can't re-use their vote cards. At the end of the game, the score cards are totalled up, and the higher score wins.

Special difficulty? Both players can memorise what's in their opponent's hand. Oh, and one of the score cards has failed to turn up to the studio, so there are only ten to be won. The obvious strategy is to bid the value, or the estimated value.

Strategy? A score of 33 will certainly win, and you could get that with 11+10+9+8 – if they're all there. Or you could try to win all the middle numbers: 8+7+6+5+4+3 is a victory combination. But what's your opponent trying to do? And which card is missing? The tactic will need to change based on circumstances, and perhaps a modified strategy.

And, thanks to number 10 vanishing into the ether, the match ends up as a 28-28 draw. The tiebreak is a shorter version: five vote cards with five score cards between 1 and 7. After three rounds, the magician leads by 7-4. He will win one round but lose the other. The next card is a 3: the last card could be a 1, 6, or 7.

What we'd do as Blue is play the odds: put down out "1" card and throw the 3 points to the opponent. If the last card is a 1, then the game's lost. If it's a 7, victory is assured. If it's a 6, we have another draw and a replay at Villa Park next Tuesday.

In the event, the final card was a 7, and the video gamer makes the final.

The rematch happened in The Repechage, Quiz Buzz was between the magician and the video gamer. This is a particularly evil game, a bit like "fizz buzz", but with the fizzes and buzzes replaced by lists of quiz answers. "You'll get the hang of it," assured co-host David.

- "Replace every multiple of 5 with a state of the USA, replace every multiple of 11 with a James Bond film."

We've got the hang of it.

"One, two, three, four, New York, six, seven, eight, nine, ten." And by stopping there, it's a wrong answer. If only they'd gone on to say "-essee".

We viewers have the advantage of a screen to see what we're meant to be remembering, but the players don't get that help.

Only one of the games went beyond the mid-teens, it seems to be difficult. The match stopped and started like a busy bus, it chopped and changed between the game and discussion about the subjects and criticism from the other players on the sofa. It never got into a flow, and we found this to be the weakest episode.

The Final was Order and Chaos: video gamer versus game designer. Pure strategy. It's played on a six-by-six grid. Order has the aim of making a row of five pieces. Chaos has the aim of preventing Order from making a chain of five. Order plays first. A draw is not possible.

We're told that a run of four with an open end wins for Order; and a run of three with both ends open must win. We're not told that Chaos will want to avoid the edges of the board for as long as possible. Except that both players can play both colours... Mind: boggles.

So, what conclusions can we draw? All of the episodes work as self-contained games. We come in knowing nothing more than the title, we leave – just six minutes later – having seen a little drama, and having seen an intellectual party game. None of these games bear much repetition, all of them entertain while they last.

The episodes benefitted from slick editing, everyone knew how to tell their story using the footage available. There were no confessionals added later, no reaction pieces from the dismissed players. The only reaction we got was in the studio, during or around the game. Were this series shown on a commercial network, we'd expect a little filler, or a little more chat, to bulk up to a commercial hour.

There were six camera angles used: a wide shot and an overhead shot of the game table, close-ups on the players, and locked-off shots of the sofa and the commentary booth. We watched all the episodes in one sitting, and eventually noticed the lack of panning shots and focus pulls. If we'd watched them once a week, as they were published, we wouldn't have made the comparison.

It's clear that Game On was an ultra-low-budget show, with no frills. We can see that a solid game will create its own tension, and that a recurring cast will become familiar characters.

This Week and Next

An interesting new show for Channel 4. The Question Jury features seven strangers answering trivia questions, unanimously. They'll pick one of their number to play for the cash. Channel 4's press release doesn't say whether that individual takes the money, or it's split between the seven. Monkey (an NBC company) makes the show, which will go out in daytimes.

The BBC has confirmed its new Saturday night talent show. Let it Shine will focus on singing and dancing, and will feature the insightful comments of Gary Barlobe. The BBC's Eurovision stars Graham Norton and Mel Giedroyc will host. Expect this on your screen in the first weeks of next year.

A development for The Chase, where families are invited to work as a team. Interesting to see how many lowball offers they'll make...

A development on Channel 4, as Fifteen-to-One has been commissioned for a couple more series. That's, what, eight in total?

BARB ratings in the week to 5 June.

- BARB has started to publish combined ITV-SD+HD numbers, so there's a battle for the overall number one. The Eastenders brought 6.8m to BBC1, Coronation Street had 6.25m on ITV-SD, but 7.55m on ITV-SD+HD. Who wins? You decide.

- Top game show was Have I Got News for You, seen by 5.05m. Pointless Celebrities European Nations Cup Special had 3.7m viewers, and In It to Win It entertained 3.55m. Both fell behind Top Gear, 4.05m.

- BBC2's top game was The Great British Sewing Bee, 3.4m. The Chase was ITV's top game show, 2.85m including HD (but excluding ITV+1, as some viewers will be counted twice). Channel 4's top game was Four in a Bed, 710,000.

- Love Island is a winner for ITV2, with 1.23m seeing the Friday show. A Catsdown repeat on More4 pulled 355,000 viewers, and Room 101 on Dave 345,000.

- Low figures for India's Got Talent on Colors, we hoped for more than 20,000. By comparison 40,000 people saw The Rock 'n' Roll Years on BBC Parliament. Expect a series.

Even though there's football, it's a busy week this week. The final of Countdown (C4, all week) is a traditional highlight; viewers who prefer less genteel pastimes will want Taskmaster (Dave, Tue). Counterpoint (R4, Mon) returns for music fans, and panel game It's Not Me, It's You (C5, Thu). A couple of imports: topical panel show @midnight (Comedy Central, 11.59pm weeknights), and unaccompanied singing Sing It On! (5*, Thu). Next Saturday is stuck in Schedule A – Schedule B weirdness.

Photo credits: Tom Scott.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.