Weaver's Week 2008-06-15

And remember: never a cross word.

Contents |

Crosswords

Program Partners / Yani Brune Entertainment / Merv Griffin Enterprises; shown on Challenge, 12pm weekdays

In the early 1990s, Britain had our very own crossword quiz, Crosswits. Tom O'Connor invited two celebrities up to Newcastle so that they could partner members of the public. The game used cunning little clues, not as cryptic as some of the ones in the newspaper, but not as simple as "Man's best friend (3)".

Fifteen years on, crosswords are back on television, albeit in a completely different show. This one is imported directly from North America, where it's billed as Merv Griffin's Crosswords. To the average British viewer, the name means nothing. To the average American viewer, the name means nothing. To game show aficionados on both sides of the pond, the name means one thing: Jeopardy! Mr. Griffin devised the format of answer-and-question, wrote the celebrated theme music, and was responsible for robbing the CBC of the great announcer Alex Trebeck.

Though Merv Griffin is barely a household name in his own household, the host of Crosswords is a famous name. Step forward aspiring soap actor Joey Tribbiani, who spent ten years on the observational documentary Friends. For reasons we've not quite worked out but are probably so boring we don't want to, Mr. Tribbiani is appearing under the pseudonym of Ty Treadway. His swift patter and good looks are still there, and as all the answers are before him, all he's got to do is read. It's the embodiment of the slick host.

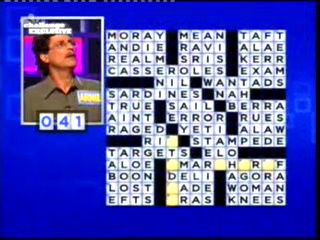

Now, the conceit of the show is that players will fill in a crossword. Unlike the British standard crossword – as much black space as white – the show uses the North American standard crossword, where black space is at a premium. Around the edges are blocks of white space, to be filled in with letters, and they're interconnected by a few longer words.

The process of solving a clue is simple. Mr. Tribbiani will read out a clue. They're on the level of "Royal domain (5)" – not obvious, but lacking in the wordplay and subtlety that are traditionally associated with crosswords in Europe. There's a short pause for contestants to push their buttons, and they're asked for their answer in the order they buzzed in. Answers need to be said and spelled, and spelled correctly.

Not every word will be solved in the main game: for instance, those words formed down by solving three or four across clues will be left unsaid. In theory, it's possible for a particularly astute contestant to use these orthogonal words to help solve the last clue; in practice, the game moves far too quickly for this to be possible, and the screen only shows the immediately adjacent letters. The producers, rather than the contestants, choose which clues to solve, and in what order.

We mentioned that the game was fast. That's slightly understating it. If the fashion in British games is for quizzes to go at a slightly languid pace, the practice here is for the quiz to stick on its afterburners and see if the speed of light is merely an advisory limit. There are typically five clues per minute, and with seventeen minutes of play in the main game, that's an awful lot of letters on the crossword. We suspect that there's a little fiddling with the crossword before the endgame, but not a huge amount.

Scoring is very simple. Most words are worth $200 (roughly £100). Long words – those of seven or more letters – are worth $300, while three-letter words are worth $100. In the first round, two players contest the game, and all the values are halved. The similarities with Jeopardy! don't end there – incorrect answers are penalised by deducting the reward for a correct answer. At points during the game, clues are deemed a "Crossword Extra", which Mr. Tribbiani never fails to describe as "a clue that only you can solve", directed at whoever solved the last clue. In these Extras, the solver can stake all or some of the money before them; they'll add that much if they give a correct answer, but lose it if they're wrong.

So far, so simple. About a dozen clues into the game, things become more difficult. Enter, stage left, three Spoilers! They take their positions on Spoilers Oh, three podia that have magically appeared behind the existing contestants. The Spoilers can't win money directly, all they can do is push their buzzers and hope to get in. The two contestants on the front row take priority when answering – even if one of the Spoilers buzzed in first, a front-row contestant will be asked if they buzz in during the moment allowed.

Should the front-row contestants solve the clue, they'll pick up the cash as normal. However, if the front row is wrong, or neither of them buzzes, it'll be thrown to the Spoilers. A correct answer will allow the Spoiler to progress to the front row – taking the place of a contestant who erred, if there was one, or the place of their choice. Crucially, the money remains on the front row, so the Spoiler inherits that amount, and is rewarded with the prize for their correct solution. A Spoiler giving an incorrect answer is wallied out of the game until another Spoiler is correct, or all three Spoilers are wallied.

At the end of the main game, the three people on Spoilers Oh have finished their time on the programme, and leave with nothing more than an airdate. The person with the less money also leaves the show, and we're not sure whether they get to take that cash. The winner does win the money, and has 90 seconds to fill in the 20 or so remaining blank spaces using the clues provided by Mr. Tribbiani. Successful completion of the grid will give them a $5000 bonus, a computer games console, and a trip to somewhere hot. At present rates of exchange, the total value of their prize is somewhere around £5000. It's close to the going rate for an hour-long UK daytime quiz, or about one-third the average prize on Deal or No Deal. Two episodes of Crosswords fill as much airtime as one visit to the Bad Shirt Casino.

We'll quickly go through the one negative from the show: the clues are bland and functional. Part of the fun of Cross Wits was in trying to solve the clues ahead of the celebs, and rightly feeling smug. Or, failing that, going "ah!" when the answers were explained. Crosswords has far more simple clues. It doesn't use the English language as a scenic drive, but as an express highway. There's nothing intrinsically wrong with that, but we prefer a little sophistication.

There are lots of small positives: we like the show's fast pace, we like the emphasis on spelling the answer, because a crossword player who can't spell will get very cross. The really good idea is the concept of first- and second-class players. Even if they're not the very first on the buzzers, the players on the front row are favoured by design. The Spoilers can only profit from the failure of the favoured players. Would a system along these have enabled Carlton's infamous King of the Castle to be a little less rubbish? Might that other one-series wonder Number One been able to squeeze this concept in?

The idea works well here, and we can see that it could be adopted elsewhere. So long as it doesn't become as ubiquitous as some other ideas, we'll be happy. The best-of-five finale is now the best-of-five cliché. The Revised Wipeout Scoring System is so old that... hang on.

Wipeout

BBC, 1994-6; recently aired on Challenge

For this review, we go back to the mid-90s, an era when the Prime Minister was unpopular, when Conservative politicians were resigning to seek a mandate for their position, and when Take That were touring to sell-out audiences.

The game is simple. Three contestants are in the studio, and – as seemed to be the television law at the time – all the men wore somewhat dodgy waistcoats. Our host, the effervescent Paul Daniels, reads out a question, and the first contestant to buzz in with the correct answer will start the first grid. The topic of the grid is related to the question they've just answered in some way, however vague.

On the grid are sixteen answers. Eleven of them are correct answers, the other five are wipeouts. Select one of the right answers, and the contestant will win money – £10 for the first answer off the board, £20 for the next, and so on up to £110 for the last correct answer. From time to time, there's a bonus prize hiding behind one of the answers, and this prize is safe no matter what happens.

There's a big however, however. If the contestant should select one of the five incorrect answers, all the money they've won so far will be wiped out, and play passes along to the next contestant.

To prevent this from happening, the contestant may pass after giving a correct answer, and play moves to the contestant on their left. This allows for a supreme level of tactics – if a contestant has two right and two wrong answers, they could pass on, and (at worst) be faced with one right and one wrong answer. Or they could have a go at finding the answer; if they're right, they can then pass and be sure of not facing the board again. This tactical play percolates a few moves back, once the obvious answers have gone.

Three boards are played in this manner, and the contestant with the least money – or fewest correct answers, in the event of a tie – is eliminated. For the remaining contestants, their money is safe, as are any prizes they've won.

We then reach the Wipeout Auction, in which the contestants see a category, eight correct answers, and four incorrect ones. In turn, they'll bid for however many correct answers they feel confident to give. Meet their bid, the contestant wins the grid. Fail – find a wipeout – and the opponent must still give one correct answer to win. It's possible for this to go back to the first contestant. First player to win two grids wins the game, and plays for the holiday.

The final game is simply a case of finding the six correct answers from 12 options within 60 seconds. It's jazzed up by having the contestant push buttons on a big plastic tablet, then running half-way across the studio to validate their answers.

Wipeout was originally a prime-time television show, going out on BBC1 at 7pm, a slot that's now occupied by Adrian Chiles and his Nationwide show. It's fun viewing for all, it's lightly educational, it's produced by light entertainment deity Roger Ordish, and some money has clearly been spent on it. For instance, the computer graphics stand up to this day – they're readable, make sense, and avoid the terrible cliché of ticks and crosses. Like Paul Daniels' previous works Odd One Out and Every Second Counts, Wipeout was light-hearted but ramped up the tension in a very clever manner, and was the beneficiary of great attention to detail.

If it's remembered at all, Wipeout isn't remembered for its brassy theme tune, or its attention to detail. No, Wipeout is now only remembered for its scoring system. Or, to be exact, a bastardised version of its scoring system. Wipeout's first round allowed for a contestant to lose all the money they'd built up in the earlier grids, potentially going from £1000 to nothing in one error. But there were checks and balances – the entire game was far more tactical than it appeared on the surface, and there was always an opportunity to pass.

Modern shows, such as It's Not What You Know, Come and Have a Go If You Think You're Smart Enough and Perseverance have only remembered the "one wrong answer costs you everything" aspect of the scoring system. They've forgotten the other parts – the fact that there was only a limited number of possible answers, that there's a pass available. They lack the depth of the original show.

This Week And Next

Ratings for the week to 1 June show that Britain's Got Talent was popular. Very popular. Popular to the tune of 13.9m people seeing the final results, beating I'd Do Anything's 7.2m into a cocked hat. The Apprentice moved to Tuesday and recorded 6.85m, while there was a good tick up for Beat the Star, which had 4.95m seeing Martina Navratilova, against 1.35m for Scrapheap Challenge. Deal or No Deal was the most-seen show on a quiet Channel 4, 2.55m guessed it was on on Wednesday. Noel managed to be a greater attraction than the century's first live commercial, which aired during Come Dine With Me, but couldn't lift its audience above 2.45m.

Britain's Got Talent dominated the digital channels, with 2.17m seeing the Saturday night follow-up programme, and a million took in the Sunday night repeat. We don't have data for More4, but Big Brother fever hit E4, with 510,000 viewing selected extracts from the audition tapes. CBBC's Hider In the House secured 170,000 viewers, the show's best score of the year.

BBC1's The Apprentice has finally reached a conclusion. This show, lest we forget, began with Alan Sugar saying that he didn't want liars, he didn't want cheats, he didn't want schmoozers. The selected candidate, Lee McQueen, openly admitted to fabricating his CV by expanding his university career from two terms to two years. We always knew that too much Sugar rots the brain.

Viewers in Ireland will be able to see their own version of The Apprentice this autumn; it'll air on commercial channel TV3, with car magnate Bill Cullen wagging his finger at fourteen wannabes. No word yet on whether ITV will buy the show, or if it might go to RTÉ's external service, starting early next year.

Those who subscribe to the email edition may be interested in Radio 4's sequence of shows paying tribute to Humphrey Lyttelton, from 11.15 this morning. Two shows come to the end of their series this week – Counterpoint (Radio 4, 1.30 Monday) and Countdown (C4, 3.25 Friday), while there's a celebration of Round Britain Quiz (Radio 4, 11.30am Thursday) to mark its 60th birthday in November.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers sign up to our Yahoo! Group.