Weaver's Week 2011-05-01

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

It may have escaped the attention of readers, but there's been a referendum campaign under way in the UK for the past six months. There's a move afoot to change the method of working out who should be the Westminster MP for your neck of the woods, from a simple plurality to a slightly more nuanced system of transferring votes.

This week's Week isn't attempting to influence your vote in any way. Our aim is to add a little colour to the debate, and perhaps illuminate what has been a theory-heavy discussion. And it means we don't need to emerge from behind the sofa to watch the various BBC or ITV Saturday night entertainments, because they make coverage of Godfrey Verydullman's speech to the Lower Snodbury constituency association look gripping. Pausing only to warn that the following article contains pictures of Jedward, we present...

A Brief History of Voting in British Game Shows

Back in the 1950s, when the science of psephology began under R B McCallum and a young David Butler, Britain was a two-party system. People either tuned into ITV, or they tuned into the BBC. Oh, there was a small fringe party, some of the chattering classes preferred Radio 3, but these people could be relegated to a footnote in studies of light entertainment.

At this stage, voting was similarly crude. Programmes like Opportunity Knocks asked its listeners and latterly viewers to contribute their opinions by sending in a postcard marked with their favourite act from the recent show. Why postcards? They needed no opening, the staff could just turn them over and put them into the appropriate pile. At the end of the week, the Opportunity Knocks team would count all the postcards, and award the victory to whichever performer had the most votes.

Convenience is important in a voting system: if an entertainer is asking their audience to work for them, they know they'll get more people involved if it's easy to participate. We'll also check to see how resilient the systems are against breaches of the "one person, one vote" tradition. For Opportunity Knocks' votes on postcards, there was nothing in the system to prevent multiple votes. Viewers who were determined could cast ten, a hundred postcards for their preferred act. Doing this would cost a postcard and a stamp, and there was always the risk of the organisers claiming there's an orchestrated campaign and disqualify the performer from the contest.

But there are other cases, ones that postcard votes didn't cover so neatly. What if a viewer liked more than one act? "Well, I like the ventriloquist, but I liked the contortionist." To have their preferences accurately recorded, they had to send in a postcard for each one they liked. This took some organisation. And what if a viewer's only response to the evening's show was "Ooh, I couldn't stand that singer", they didn't want someone to win? In that case, the viewer had to vote positively for all of the other performers on the programme, and that took an awful lot of organisation. Only the most determined viewer would even consider this course of action. The voting system used by Opportunity Knocks was simple: it worked when there was a straightforward choice between two alternatives, but proved more difficult to navigate when there were six or eight choices.

We'll bring the narrative forward to the 1970s, and shows like Search for a Star (2). Again, it's a talent-spotting programme, though this time without any public involvement. All of the marks are given by a series of regional juries, ten panels of ten people, each awarding a score out of ten. How did they come to these marks? Such information is lost in the mists of time, all that the viewing public got to know was the total score each jury had given for the performers. Cheating was impossible: this was one jurist, one mark out of ten.

This arrangement allowed more precise expressions of judgement: not only could the panellist say that they believed this week's ventriloquist was better than last week's, but they could say by how much they held that view. If, for instance, last week's ventriloquist had scored a total of 600 points (6 per panelist), a slightly better voice-thrower might pick up 7, and an astoundingly good one could be heading to a 9.

During the heats, voting was in a number of entertainment categories, so such comparisons were easy to make. The final pitted the various category winners against each other, and so many were the possibilities for tactical voting that it was far more simple to just give marks sincerely.

The public had to be excluded from Search For a Star because the producers wanted to have the result in the same show as the performances. This had been the traditional hallmark of the Eurovision Song Contest, where Western Europe came together to spend a night looking for the most middle-of-the-road song, and gawp at the presenter's wonderful / abysmal English, French, German, and Italian. The Eurovision Song Contest has used three different sorts of voting systems in its lifetime. In the early years, the most common arrangement was for each competing broadcaster to assemble a jury of 10 people, and each would give one vote to their favourite song. This was the Opportunity Knocks scoring system, with the vagaries of the international post network replaced by the only slightly more reliable international telephone network. For a few years in the early 70s, the plan was for each broadcaster to send two people to the competition venue, where they would give marks out of five for each song. This ensured the result would be given on the night, without waiting for the last vote from Belgrade, and should be familiar as the Search For a Star arrangement.

Sue Lawley explains how ROVER works.

Eurovision's most familiar voting system was first used in 1962, and has been employed each year since 1975. Here, it's not just the top song that scores, but the top few songs, and their ranking is important. Originally the system awarded 3 points for the jury's collective favourite song, 2 for the next most popular, and 1 for the tune in third place; it's since been extended to give points to the top ten places in each broadcaster's rankings. If the collective feeling on the jury is that a particular song is brilliant, they're able to throw all the points behind it. If they believe a certain song is rubbish, they can arrange for it to score nothing. This idea is known to psephologists as a Truncated Borda Count – truncated because it only considers the top few places, and a Borda count allocates more points to better-preferred options. The proof is in the pudding, and it's rare for the Eurovision winner to be completely without merit when compared to the rest of the entries.

By the 1980s, technology had moved on, and suddenly television producers had worked out that there was a telephone in every home. Actually, they'd made this intellectual leap some decades earlier, The Golden Shot wouldn't have worked otherwise. What really made the difference was the arrival of computerised call-counting systems, and the possibility of charging callers a premium. A revived version of Opportunity Knocks was the first show to exploit this technology, and the host of spectacular live formats was brought in to host it. Bob Monkhouse threw the lines open, viewers cast their votes, and on the very same night he would read out the winner as decided by the viewing public. All for less than the price of a postcard and second-class stamp, and with less chance of the Post Office losing the message.

And all with the distinct possibility of some ballot-stuffing. Operatives of the British Telecom company were able to provide a readout of votes and little else. Determined voters could spend £25 on a hundred votes, and they probably wouldn't be caught. This system shared the same particular weakness for people who wanted to vote negatively, they still had to call every number except the person who they wanted to lose.

As the years wore on, BT and other telecoms providers became accustomed to unusual televoting patterns – an early or a late surge for one candidate, call logging systems that enabled them to check for egregiously multiple voters. Eventually they worked out how to determine where calls were coming from, and sort them geographically to see if Scotland preferred something different from Wales. This was completely irrelevant for such frippery as Channel 4's Star Test, where young people were asked to call in and say if they believed Clint Boon from the Inspiral Carpets was or wasn't telling the truth to the computerised inquisitor's personal questions. It's just an entertainment, with two pre-recorded outcomes.

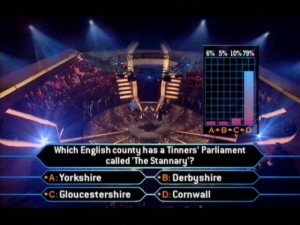

78% of the vote for D. No need to consider second preferences.

Other shows had their own style of marking. Ready Steady Cook threw the judgement over to the audience, who would put up their cards to vote for the red or green pair. Later in the 1990s, Who Wants to be a Millionaire asked its audience for help on some questions, with each person choosing the one answer they would go for, and the ratio of people giving each answer informing the contestant's decision.

Into the new millennium, and Big Brother had a novel voting system. The contestants would decide, amongst themselves, which would face an election this week. The contestant – or, occasionally – contestants – scoring the most first-preference votes in this election would be eliminated from the competition. Psephologists saw this as being a bit like the nomination of party candidates in the Westminster system – the lazy side of the house would nominate someone from the busy side, the busy side would nominate someone from the lazy side, and the viewers would cast someone out.

Big Brother's voting system was carefully constructed – the winner would have to face the public vote eventually, but they may not have to do so before the final. If someone is particularly hated in the outside world but loved amongst the contestants (Nick Bateman, for instance), they'll never be up for nomination and can never be voted out. Similarly, if someone is particularly loved in the real world (series 2's Paul Clarke), they'll survive vote after vote after vote.

By voting to evict, viewers are asked to consider who they don't want to win at that particular moment, perhaps considering that if they don't vote someone off now, the chance may never arise again. Such considerations were absent from 2000's other big new show The Weakest Link, where all players were up for eviction in each round of competition. Contestants on Link could see where the other votes had gone, and alter their plans accordingly, perhaps getting rid of players who were already unpopular. This information was jealously guarded on Big Brother, where even the merest squeak about who might consider voting for whom was a capital offence.

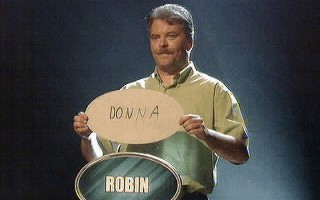

One vote for Donna. But will the other votes follow the facts?

Perhaps those on The Weakest Link felt some pressure to conform – someone in the group had named Bill as a weak player in the last round, he's had a bad one this, we'll gang up on him. There were additional incentives to vote someone off the team in other shows – ITV's The Great Pretender gave additional cash for everyone booted, and Channel 4's Unanimous would only come to an end when the panel agreed on a single winner amongst themselves. In each case, a secret ballot was changed by the subsequent revelation of votes.

It took a few years for Big Brother's two-stage elimination to become familiar – 2002's Fame Academy tried a three-stage eviction process, with contributions from the pap panel, the viewers, and the fellow contestants. No-one understood it, least of all titular head Richard Park. It wasn't until The X Factor debuted in 2004 that the process became formalised – the public would stage a simple plurality vote to determine the two most likely evictees, from which the expert panel would choose one. This process, or something very much like it, has been used on Strictly Come Dancing and So You Think You Can Dance and all the Lloyd Webber casting shows. Even the talent show When Will I be Famous had a pre-filter, with selected members of the public weeding out some of the acts from the public phone vote.

Another prime-time entertainment programme that relies on voting is the BBC Sports Review of the Year, which ends with the award of the corporation's Sports Personality of the Year award. Unlike the Eurovision, this bauble has seen radical changes to the voting procedure in recent years. Until about 1996, the award was given from responses to coupons in the Radio Times, or names sent in on the back of a postcard. Internet voting was added in the late 1990s, reducing the cost of entry. There were inevitable campaigns to fix the vote, with fisherman Bob Nudd being disqualified one year on the grounds that his sport wasn't a sport but a pastime. In 1999, voting changed so that the postcards and emails would form a top six, from which a telephone vote on the night would decide the winner. That changed again in 2006, so that the opinions of the London newspaper journalists formed a shortlist of ten entries, and the public could choose only from those people pre-selected by the gentlemen of the press.

The Sports Personality of the Year award is perhaps the most high-profile example of a ballot gone wrong. The initial selection of ten is subject to the whims and prejudices of Fleet Street journalists, there's always a boxer, never a rugby league player, and heaven forfend that there's a woman who plays a team sport on the list. The viewing public has absolutely no say in who gets on the list. Moreover, there are organised campaigns to back certain finalists above others. In 2008, the cycling fraternity chose to back one of four nominees from that sport, and their chosen one duly won the award. In 2010, organised campaigns for a jockey and darts player gave both of them places in the top three.

Sports Personality's problem is that the award is of sufficiently high stature, and the barrier to multiple voting is so low, as to make it worthwhile trying to manipulate the election. The organised campaigns can only get away with it because there's a single round of voting. Prizes that the BBC values, such as Strictly Come Dancing, employ round after round after round of voting, only ever removing one or two entrants per week. This can change the outcome: if there had been just one ballot on last year's Strictly, and the person with the highest number of public votes had been declared winner, Ann Widdecombe would have taken the crown.

These shows are the closest in concept to the alternative vote system that's not under discussion up and down the land. Watch everyone perform, and vote for the one candidate you liked the most. If it proves that no-one else agreed with you, then go back and vote for someone else. Well, roughly. The alternative vote saves a bit of time by asking people to specify their choices in advance, so (using names from 2009's The X Factor) viewers fill in a paper that goes 1) Jedward 2) Rachel Adedeji 3) Danyl Johnson, and so on until indifferent to the result. (Does anyone care which of Kandy Rain and Miss Frank wins? Can anyone remember the difference?)

Initially, our one example vote is for the extremist candidates, Jedward. While they're popular in the beginning, Jedward eventually fall behind Joe McElderry, and Olly Murs, and eventually are stranded at the bottom of the pile. At this point, our vote would go to Rachel, but she's long gone, so it transfers behind Danyl. When he's eliminated the following week, we're indifferent to the outcome, and our vote dies. At no point do we have more than one vote, it just moves about different piles. Our vote is counted nine times in total: seven times for Jedward, and twice for Danyl. Someone whose first preference was for Danyl also has their vote counted nine times. Someone whose first preference was for Olly Murs has their vote counted nine times for him.

The net result of all these run-offs and whittling down is a final contested by people who are popular amongst a broad swathe of public opinion (read: a bit middle of the road) and the most popular amongst them wins. And, of course, Joe McElderry promptly lost the bonus round to an internet prank, but that's life for you.

Doing this sort of instant run-off over the telephone is tricky, and it's only been tried the once before. In 1987, the erstwhile Radio Active ran its "Mike Says: Here's A Bit of Talent" competition, and staged an alternative vote for its final round. Here's the telephone script:

- "This is the Radio Active Spot That Talent phone vote. Please vote for the act you liked best after you've heard the tone.

If you liked act A best, say "X"; if you liked act B best, say "Y"; and if you liked act C best, say "three".

If you liked A and then B, say "fourteen"; if you liked A and then C, say "Fanshaw"; if you liked B and then C, say "Liverpool".

If you liked B and then A, say "forty-one"; if you liked C and then B, say "washnaf", and if you liked C and then A, say "I liked C and then A".

Finally, if you liked A, B and C equally, there was no point in you phoning up, so you must be a complete [tone]."

And if all this is still too complicated, there's always the option of giving up and letting someone else make the world to their preference. That's Fighting Talk, and we discussed it last week.

Ultimate Big Brother

An OFCOM complaints bulletin came out last week. As was widely reported, the regulator found there was nothing unduly provocative in The X Factor's final, and its press release intimated that elements of the press had inflamed the situation by publishing pictures that weren't actually broadcast.

More interesting was the privacy complaint by Nadia Almada, a contestant on last year's Ultimate Big Brother competition. Readers (the two or three who watched the programme without falling asleep from boredom) might recall that Ms Almada was involved in a running feud with Coolio, whom she accuses of harassment and bullying over her status as a transgender person. Her complaint revolved around two particular rows during the competition – one on the third night, another the following morning – and the general tenor of her portrayal vis-a-vis Coolio.

On the third night of competition, Coolio survived an eviction vote against John McCririck. He strutted around the studio, bragging that "this is my house" and "the game starts now". All of which was nonsense, of course, he's no Brian Dowling. Only Nadia rose to the bait, and there was a heated row between them. The atmosphere wasn't helped by the dour clown introduced to mess with Nikki Grahame's head.

The following morning, Coolio secreted all of Nadia's many shoes in a duvet cover. Again, an argument ensued, in which people called each other things like "blighter" and "count". Though the unedited transcript differed from the program as broadcast – footage was edited, and Channel 4's bleep machine was wheeled out – OFCOM found that nothing was amiss in either of these particular incidents.

OFCOM then turned its attention to the general portrayal of Ms Almada and Coolio. Nadia used the diary room to address the nation, voice her opinion of her actions, and fret about her loss of dignity. Coolio was also seen in the diary room, discussing matters with the Voice of Phil Edgar-Jones, and agreeing to leave. OFCOM reported, "Having watched the full unedited footage of Coolio's diary room conversation, it was clear to OFCOM that, while his relationship [with] Ms Almada was not the only issue put to Coolio by the programme makers, it was a contributing factor to his decision to leave the house."

It seems accepted – by both Ms Almada and the Channel 4 / Endemol production team – that Coolio probably did step beyond the boundary between intellectual curiosity and personal abuse, and was warned by the producers. Opinions differ as to whether these warnings had any effect – it's notable that Coolio doesn't seem to have been contacted for his comments. It's certain that none of this made the final programme as broadcast. Viewers didn't see the contentious discussions, in part because that would doubtless have sparked off a further flurry of OFCOM complaints. Having not seen the abuse, it would have been exceedingly unusual for Coolio to be reprimanded on camera for something that had happened off camera.

OFCOM, however, has taken a wholly remarkable view – if something isn't shown, it can't cause offence to anyone. Channel 4 feared an adverse OFCOM ruling if it showed Coolio berating Nadia, so it didn't show that footage. Having not shown the attack, it can't show Big Brother's response. This clearly and obviously wasn't a true and accurate depiction of what had happened, and we can't help but feel that it was misleading – it certainly wasn't obvious to this column why Coolio suddenly withdrew from the competition. Did this cause unfairness to Ms Almada? Very possibly, because it gave the impression that Nadia's shoes were the only reason for Coolio's exit, and not his illiberal views.

Readers may wish to compare against the only other OFCOM decision stemming from a complaint by a Big Brother contestant – Dawn Blake from 2006, adjudicated two years later. Then, this column concluded that OFCOM may have gone out of its way to adjudicate in favour of the producers. This time, we find ourselves considering the same evidence as OFCOM, but reaching a wholly different conclusion, and one that can only be supported by an axiom we do not believe. This column believes that it is possible to mislead by omission: OFCOM clearly does not.

This Week And Next

Pacific Quay is seeking a new anchor tenant. The BBC's Glasgow operation had Anne Robinson brought in by seaplane last year, bringing her hit show The Weakest Link with her. Now, we hear that Ms Robinson is to leave her programme next spring, and she won't be replaced. Clearly, the BBC has learned from the Ed Tudor-Pole incident. New quiz programmes are already being thought up, as are possible non-gamey replacements in the schedule.

Ratings for the week to 17 April are in, and, gosh. Britain's Got Talent is back, and back to the tune of haven't 9.75m people got better things to do with their Saturday night? Masterchef rustled up 5.8m viewers from flour and eggs, and Have I Got News for You took 5.45m viewers and one superinjunction. Sing If You Can debuted to 4.85m, and The Cube had 3.3m peering in. With Young Paxman leaving his Monday slot, BBC2's biggest game show was Great British Menu (2.15m) and C4's was Come Dine With Me (1.85m).

The Mastermind grand final was also seen by 1.85m people, as was ITV2's Celebrity Juice. Which show regular is smarter: Ian Bayley or Fearne Cotton? Answers on a postcard...

After the party, it's the hangover, with very few new shows of note this week. Interesting programmes include the final of Great British Hairdresser (E4, 10pm Monday), featuring a guest appearance by Vidal Sassoon; and the start of a new series of Survivor (TG4, 7.30 Wednesday), but that's only for viewers in Ireland. There's all sorts of schedule-related shenanigans from the election results on Friday, do check carefully before viewing. More 4 gets in the mood for the Eurovision Song Contest with a double-bill of documentaries on Saturday night: The Secret History of Eurovision (9pm) and Sounds Like Teen Spirit (10.40), the latter at the 2007 Junior contest. Highlight of the week is The Quite Remarkable David Coleman (BBC2, 9pm Tuesday), a profile of the man who hosted A Question of Sport for absolutely years.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.