Weaver's Week 2011-06-19

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Coming up, all sorts of fashions, and a quick look at the rumour mill.

Contents |

Four Rooms

Thames for Channel 4, from 17 May

Here are four dealers in rare and collectable items. They've come to a disused warehouse with wodges of cash, and some decorations to make one of the rooms look a bit nicer. They'll be spending an awful lot of time in that room.

Here are some people with something rare and/or collectable to sell. They've come to a disused warehouse, and hope to relieve one of the dealers of some of their wodge of cash. To do this, they'll negotiate with the dealers, looking to secure a mutually-agreeable price.

As ever, there's a twist. The sellers can only see one dealer at a time, and can only see each dealer once. As soon as they walk out of that dealer's room, the offers are consigned to the oubliette, never to be seen again, living on only as phantom deals, memories of numbers in the seller's head.

The regular staff of the show are the four dealers, their personalities are projected through their rooms. Andrew Lamberty has an avant-garde room: chairs with oversized arms, a table off to the side, a lamp-stand made out of large metal chains. He gives off a serious, no-nonsense air, that he knows what he's doing and won't brook for much negotiation. Gordon Watson has comfortable armchairs, a sculpture in the shape of an hourglass, and the room is overlooked by a painting of a young woman wearing a skull-mask over half her face. It might suggest he gives an easy ride, but there could be a sting in the tail.

If we're being honest, these are not the dealers who attract attention first of all. Jeff Salmon is a larger-than-life character, he looks as though he might ask us to pick a card, any card. His room is dominated by a large modernist glass table, the small black chairs are noticeable more for huge metal curves than for the actual seat. On the wall, a fuchsia picture of Marilyn Monroe looks down on proceedings. Emma Hawkins prowls the game like a sleek animal, the chairs in her room are like deer, with antlers sticking out of the top and fur-lined cushions. There's an abstract sculpture and painting in the room, showing that this dealer has an eye for the bizarre.

Every show needs someone to keep order, and to remind the contestant and viewer of procedure. Anita Rani fills this role, and she's a good choice for the job. She's not there to dominate proceedings, the sellers and the dealers are able to speak for themselves, and always take that opportunity. If this show had had a Name presenter, say it was Dickinson's Four Rooms, then the host would have had to interject and give advice. Anita Rani doesn't, she keeps the wheels turning and knows when to keep quiet, which is admirable.

Most segments of Four Rooms follow a similar pattern. We see a valuable item: it might be a collection of model cars, or a 1960s-vintage Dalek prop. Anita provides some information to set the artefact in context: what it is, where it's come from, how much similar items sold for in the recent past. We might see the owner talking about their item with the dealers, we might not. Then Anita explains the rules, and asks them which dealer they wish to see first.

The negotiations begin with the dealer explaining what they think about the item, and setting the mood for their work. Then they'll name a price, the seller will decline and perhaps names a far higher price. If there's room for compromise, we'll see them working towards that point: if there isn't, we'll get a bit of an explanation.

If there's no deal, we'll repeat that process for the remaining dealers: again, the seller chooses which one they see next, and next, and next. If the item does get sold, the remaining dealers are called out of their rooms, and the ones who didn't meet the vendor are asked how much their opening offers would have been.

Now, we have to ask the question: is Four Rooms a game show? We reckon it just about squeezes through, as the presentation (particularly Anita's voiceover commentary) is couched in a particular language. Selling the item is a victory, selling the item for the highest possible price is a big victory. Leaving the warehouse without selling it is a defeat. It's not the most clear-cut game show, but we reckon it qualifies.

The beauty of Four Rooms is that viewers can appreciate it in many different ways. As we've just noted, there's a way to determine a winner and a loser from every deal. People who want to see valuables valued will come away with at least one number, and an insight into the range of opinions in the art of pricing.

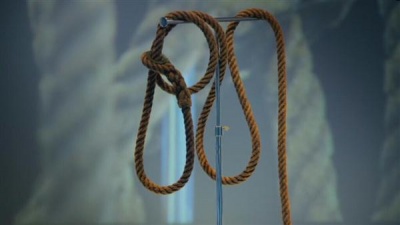

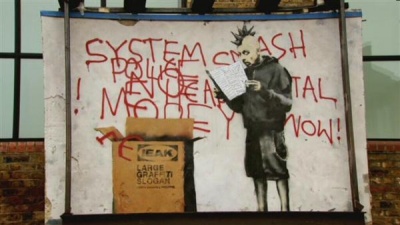

Some viewers will be interested in Four Rooms as a test of negotiating skill, whether the seller or the dealer will come away with the better deal. For this, we would ideally need to know how much the dealer was later paid for the item, if they made a profit or a loss. Even in the confines of the rooms, we can appreciate a psychological drama, not least the high-stakes battle between Jeff Salmon and a couple who wanted to sell a wall containing a Banksy piece. Six-figure prices are being bandied about like they're going out of fashion.

Or, if none of that is to your taste, you could appreciate Four Rooms as a grab through contemporary art and memorabilia. Anita Rani's commentary provides some context for each of the items under discussion, and that doubles as a thumbnail sketch of a piece of 20th or 21st-century art. A brief history of Banksy, for those who know the name but not the works. A brief history of the model car, or of Doctor Who, for anyone who's been living under a rock.

Negotiation. Victory. Numbers. Art. Four rooms. Four ways of viewing the show. It's just a shame that so very few people are, and we're jolly pleased that Channel 4 has stuck with the programme and not exiled it to 4Poorer. It deserves better.

Game theory

And now, a blast of mathematics, because Four Rooms is subject to some game theory analysis. Readers who find their eyes glazing over will wish to skip this bit, we're reviewing Style the Nation in a little while.

First, the warning. This whole analysis works only if you believe an unrealistic assumption: that everyone concerned aims to maximise their personal profit, without regard for how they look on television. Game theory works if and only if everyone involved is a psycopath or an economist.

Mathematics has a known result – called the Secretary Problem – that says someone who will receive a number of take-it-or-leave-it offers should reject the first 35% of people they encounter, and accept the first offer better than the ones they've already rejected. If this sounds familiar, we discussed it in our review of The Love Bus late last year. When applied to Four Rooms, it says that the seller should reject the first offer out of hand, and accept any offer higher than that.

We must assume that both dealer and vendor are aware of the Secretary Problem, and have been able to plan accordingly. Information in this game is asymmetric: the dealers don't know whether they're the first to see the heirloom, the last, or somewhere between. Only the vendor knows this information. Nevertheless, the dealer can adopt a strategy that is blind to where they are in the chain.

Assume, initially, that the dealer is first to be seen. Whatever offer they make is going to be rejected, because they're the first dealer. They can offer 10 times the fair value, but it's going to be rejected. They can offer 10p, as in ten new pence, but it's going to be rejected. The value of the bid doesn't particularly matter, but we can simplify it as Far Above the fair value, Far Below, or About Right.

Now, consider dealer number two. They're certain to see the item, because the vendor knows the mathematics, and uses the first offer as a reference point. If the first dealer went Above, the second needs to go Above-and-a-bit. If the first dealer bid About Right, the second needs to follow their own About Right strategy and hope their valuation is higher than the first, or follow the Above strategy. If the first dealer bid Below, then any higher bid will win. A similar analysis applies for dealer number three, and for dealer number four, with the proviso that they may not get to see the item.

It's clear that if the first dealer ever follows the Above strategy, then the vendor will only sell to someone following Above. If the first dealer follows the About Right strategy, then the vendor will sell to anyone following Above or About Right. If the first dealer follows Below, then the vendor can sell to anyone following any strategy.

But what sensible antiques dealer would bid well Above the asking price? Paying ten times the par value may guarantee them possession of the artifact, but it'll also leave them with a spectacular loss. So no-one is going to bid Above. So the strategy changes: if the first dealer plays About Right, the others will have to follow that strategy. Only if the first dealer plays Below and the next one plays Below will he win the item at a clear knock-down price.

If we impose the additional condition that the vendor has to sell, then the dominant strategy changes again. Someone has to win, and if the play reaches dealer number four, they can adopt the Below strategy and force a win. Knowing this, there's no reason for any other player to offer the About Right value – they could be playing in fourth place, and pay hundreds of pounds for something they could have for pennies. Quickly, the problem degenerates and degenerates, until the final strategy is to bid as follows:

One new penny, with probability 5/16

Two new pence, with probability 1/2

Three new pence, with probability 3/16

We're pleased to see that all of this theoretical discussion (which took us ages to work out, and we're jolly well going to publish it) remains completely academic, because the dealers are making sensible, honest offers. We applaud their fairness.

Style the Nation

Two Four / Monterosa for T4, 4 June – 16 July

This review mostly based on the show from 4 June

Once again, we bump into The Fashion Police. According to host Nick Grimshaw, the objective of this programme is to give lots and lots of publicity to the advertiser-funders, a high street fashion chain pumping out identikit clothes that are designed to wear out within six months.

Er, no it's not, the programme is intended to give someone a chance to win a year's employment arranging clothes and working out styles that can be photographed and displayed on catwalks, then walk off the shelves and can be mass-produced at spectacularly low cost by people in the developing world paid a pittance. That's not only a pittance by Western standards, but a pittance by their local standards.

Part one of the show has Grimmy telling us about the programme's internet connectivity – it's got a website, and it's not afraid to use it. One of the finalists will apply over the intertubes, rather than attending auditions in such fashion hotspots as Cardiff, Glasgow, or Birmingham. All of the voting on the programme is done over the internet. We can hear the groans from the BBC compliance unit already, because the corp believes that internet voting is too prone to manipulation and fakery. This needn't bother Style the Nation, because manipulation and fakery are what the industry is about.

This show is so up-to-the-minute that it tells us about #stylethenation, the programme's IRC channel. We presume they have a gopherspace presence somewhere, because all shows need their own little squeaky thing. Which brings us to the Fashion Police's representatives on the programme. Giles Deacon is a fashion photographer, and Barbara Horspoll is the sponsor's creative director and will end up as the winner's boss.

Barbara claims that a successful stylist needs passion, fire, and instinct. How is one to measure these qualities? Can they be measured scientifically? If they can, why don't we wheel out Horspoll's Fashionometer, to crunch the numbers and determine the winner by automated means and the cold steel of logic. What role does the voting public have in this programme? If these things can't be measured, then they're opinions, and why should the Fashion Police's opinions count for more than the next person's? They may have a great track record in picking winners, but they don't remind us of all the losers they've tipped, and never submit their efforts to rigorous scrutiny.

Joining the resident Fashion Police officers is a guest judge each week. On the opening programme, this role should have been filled by James Brown, the celebrity barber and hat-wearer. Readers may recall that we endured him on Great British Hairdresser a few months ago. In the week before transmission, Mr. Brown used a racial epithet that would have had Phil Edgar-Jones reach into the Big Brother studio and sling him out, hat first. T4 is nothing if not consistent, and Mr. Brown did not appear on the show: his place was taken by Sophie Ellis-Bextor, a Blue Peter silver badge holder.

Part one shows some footage of auditions, held in a shopping centre somewhere near London. Grimmy is shown picking out half-a-dozen possibles. Do we believe that these are his choice, and not those of the Fashion Police's special constables, employed to keep order and make sure no-one who doesn't meet their exacting standards appears on screen? Because it really wouldn't be good for the advertiser to have their product advertised by someone slightly ugly, or a bit old, or otherwise different from their target customer.

In the second part, the six possibles are reduced to two plausibles, and there's footage of them going shopping with an arbitrary budget and an arbitrary time-limit. They've been set a challenge to style three models, for various hypothetical scenarios (in this episode: beachwear, music festival, first date) and with a restriction (for instance, there's got to be some lace involved). Just when they think they've got it all worked out, Grimmy comes backstage with an additional challenge: to create an additional outfit from clothes provided by the producers.

This leaves a rather large hole at the start of part three, so there are some blatant fillers. There's discussion of the fashion choices of some celebrities in the news – in this case, the new members of the critical panel for The X Factor. Grimmy has a "what style are you?" quiz that we just know is going to give completely incomprehensible results: apparently, this column is on the road to bohemia but isn't there just yet. If our fashion sense were a football team, it would be 1860 Munich.

There's also a question for the viewers to answer, and a few responses are modelled, before fashion correspondent Alexis Knox or Kat Byrne (who we've already seen imparting nuggets of nonsense to the contestants) tells people what they should wear to music festivals. Ask her again next year and she'll give an entirely different answer. That's how the fashion industry operates: there's never an answer right for all time, just one right now.

Finally, we reach the big catwalk moment, where the two wannabe stylists parade their four outfits for the delectation of the Fashion Police. The models walk along the show's catwalk, a nearly-complete ring with part at the back concealed. In the middle of the circle is the studio audience, kept in their place, below the Fashion Police and the designers. Patrick Watson designed the set, and while it's clearly not had a huge budget and will look dated very quickly, it does the job required of it.

The designers are exhibiting for votes, and their friends and family are doubtless voting early and voting often already. In the three-minute voting window, The Fashion Police take statements, saying what they like and dislike. Three minutes to vote? That's nothing! Even So You Think You Can Dance gave longer. While the votes are counted and/or verified, there's a (clearly pre-recorded) performance by this week's musical guest, silver Blue Peter badge winner Sophie Ellis-Bextor. Hope she's being paid a double fee.

"I'd like to know what beach anyone goes to dressed like this," says one of the Fashion Police officers. Unwittingly, she's put her finger on this show's problem: it presents idealised solutions to abstract problems. Like economics, the fashion stylist attempts to get somewhere close to the real world, but doesn't quite get there. It's kept at a level of abstraction and generality, distant from the regular person's experience.

"We're minutes away from finding out the winner" says Grimmy no fewer than four times in this final segment, launching into the most unlikely catchphrase of the year. A winner is declared, congratulations are offered, advice is offered, and the show is over.

We find it hard to generate enthusiasm for this programme, just as we find it hard to generate enthusiasm for the advertiser-funder or their products. It's there, it does a job, and if no-one remembers it in a year, it won't be a huge surprise. The show is so controlled and polished that one of the job titles in the credits is "Brand Partner Exec for Sponsor". The show remains completely and totally on-message, and replaces any life it might have had with a completely artificial sheen.

There is just one thing that might save this programme from the memory hole, and it's only visible in the opening and closing titles if you know what you're looking for. Down at the bottom-right corner is a double-P sign, indicating that this programme contains product placement. Somewhere, someone is wearing clothes that have been put on the programme by its advertiser-funder. Our money's on the item that went "wear this to a summer festival, and it'll be obvious you crib your style from the Fashion Police off the telly." Whatever, Style the Nation is the first product placement show we've reviewed, ensuring it a footnote in history.

This Week And Next

A few rumours circulating the shows we call game. According to an unconfirmed twitterer, Paul Sinha is to join the line-up of The Chase; we'll believe this one when we see it on official ITV headed notepaper, complete with a little knitted monkey in the bottom corner. According to another rumour-monger, Celebrity Big Brother reaches Channel 5 on or about 10 August; we understand this fits in reasonably with the channel's next BB spin-off series, of which more anon. And one confirmed report: the BBC has signed for a localised edition of The Voice Of Holland, yet another singing competition with the gimmick that the judges don't see the competitors in their first auditions. It'll be on BBC1 next year.

Ratings in the week to 5 June, and Britain's Got Talent is the nation's most popular programme. Finals Week peaked on Saturday with 11.35m seeing Simon Cowell crowned the surprise winner. The Apprentice led BBC1's ratings, 7.6m saw Wednesday's episode. The Popstar to Operastar filler in BGT was seen by 6m people, over a million more than Sunday's actual contest. The Apprentice You're Fired drew 3.5m to BBC2, where Great British Menu finished with 2.75m. On Channel 4, daytime Four In A Bed (1.4m) proved more popular than primetime Three In A Bed (1.25m). Four Rooms hasn't made the channel's top 30 in its first three weeks.

Inevitably, BGT leads on the digital tier: a smidgeon under 2m for Saturday's More Talent on ITV2, 1.43m saw the performances on ITV-HD. Come Dine With Me attracted 850,000 escapists to More4. CBBC's Gory Games proves to be a hit, 380,000 saw the week's biggest show; Alexander Armstrong's Big Ask was Dave's most-watched panel game, with 250,000 tuning in. We hope to review that, and the channel's Compete for the Meat, next week.

Today is finals day in the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World (BBC2, Radio 3, Radio Wales, Radio Cymru from 5.30). Johny Pitts has recovered from his zorb-ball adventures, so he joins Myleene Klass in Escape from Scorpion Island (BBC2, 4.05 weekdays). And if your life has been missing In It to Win It, relief is at hand (BBC1, 8.10 Saturday, subject to delay in the event of Andy Murray). Or you could be watching Les Chefs (TV5, 8pm Saturday), Masterchef doesn't get more French than this.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.