History of the Game Show

This Good Game Guide provides a primer on how game shows have developed in Britain from the beginning of television to the present day.

Contents |

The early days

The BBC began the world's first high-definition, regular TV service from London in 1936. It wasn't until two years later that any form of game show appeared. In fact, the very first game show ever shown was very possibly the worst ever.

Spelling Bee was broadcast on 31st May 1938, transmitted live from the BBC studios at Alexandra Palace. Hosted by Freddie Grisewood, the panel of guests were asked to spell a series of words. And that was it. The host was bedecked in schoolmaster garb as a way of adding kudos to what was otherwise a light-hearted quiz - a technique that countless other shows would use throughout the century. It was not until the late 80s that children were treated as young people rather than schoolkids.

Spelling Bee in action

Spelling Bee in actionTelevision closed down during the Second World War, and even when the service returned most of the programmes shown throughout the rest of the 1940s were largely forgettable.

1950s

The first game show whose name still means anything to anyone is What's My Line?, which ran on the BBC from 1951. It was another simple panel game, nevertheless it ran in numerous different versions on two different channels through to the mid 90s. The programme was the first US import of a Goodson and Todman show - many more were to follow.

A What's My Line panel.

A What's My Line panel.The BBC's monopoly was broken in 1955 when the government decided that a commercial station (ITV) should come into being. Its two defining characteristics were that it would carry commercials and be formed from a number of local companies. This localised nature led to some game shows being shown in some parts of the country but not others, a situation which still exists today. Since the content of such programmes is frequently non-dependent on the area in which the show is broadcast, this is still something of an anomaly for the game show fan - but nevertheless a better situation than is currently endured in the USA where few programmes are syndicated. Although there are still a few anomalies in the Scottish regions, in general all prime time game shows in the UK can be seen throughout the country.

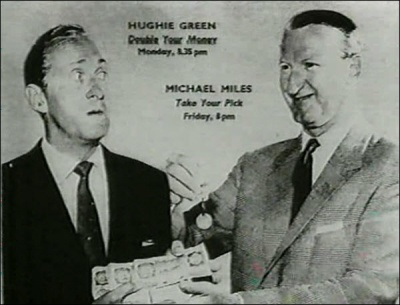

With commercials came the advent of prize funds. Associated Rediffusion, one of the ITV franchise companies, hit the big time with Take Your Pick, the first show to offer money prizes. Companion show Double Your Money offered a top prize of £1000. Thereafter, the money ramped up quickly - one contestant won over £2,000 in 1956 and another won over £5,000 in 1957. It would not be until 1993 that it was possible to give away unlimited prizes - until then, the top limit was around £6,000 per show.

In the mid to late 50s, Britain went quiz show mad, reflecting the similar fever in the USA. Game show fever reached its height in the autumn of 1958, when the ITV network was putting a quiz out in prime time six nights a week (from Sunday to Friday: Dotto, Keep It in the Family, Twenty-One, Spot the Tune, Double Your Money and Take Your Pick). The long list of hit shows during this decade included Criss Cross Quiz, Dotto, the The 64,000 Dollar Question, Concentration and Twenty-One. Many of these shows were imported from the USA, a trend which only slowed down in the 1970s.

Twenty One

Twenty OneThe big money shows didn't all have their way - celebrity panel games such as I've Got a Secret and Tell the Truth also added to the mix. But none of these matched the success of Take Your Pick and Double Your Money, which both ran until 1968. In fact, the only reason these two shows ever ended was due to Associated Rediffusion losing their regional licence in a local franchise reorganisation ordered by the government. People are Funny and Make Up Your Mind showed early signs of using stunts and practical jokes - a key theme of the mid 1980s onwards. Crackerjack provided panto-style fun for schoolkids from 1955.

As documented in the Robert Redford film Quiz Show, Twenty-One in the USA caused the great "Quiz Swizz" when Charles van Doren was found to have been given the answers to questions in advance. It's less well known that Twenty One was dropped by Granada in the UK when a contestant here also claimed that he had been given "definite leads" to the answers.

1960s

With Take Your Pick and Double Your Money maintaining their remarkable headlock on the audience figures until their unfortunate demise, very few other shows were able to get a look-in. The introduction of a second BBC channel in 1964 did little to alter the outlook, since it had been created to provide alternative higher-brow programming than mere quiz shows, and for several years Call My Bluff was the channel's only game show of any note. It wasn't until near the end of the decade that the BBC finally came up with a hit game show in the somewhat low-brow form of Jeux Sans Frontiéres. Meanwhile back on ITV, the unashamedly highbrow University Challenge was perhaps the most surprising hit of the decade.

Two teams on University Challenge.

Two teams on University Challenge.Early attempts were made at high-tech gimmicks, such as the Telebow in The Golden Shot - a show that reached popularity when it was moved into the traditional graveyard slot of Sunday afternoons. From the late 60s to early 70s, Hughie Green's long-running talent show Opportunity Knocks finally began to hit the ratings top 20, thanks to some long run commissions.

Bob Monkhouse and the Golden Shot

Bob Monkhouse and the Golden Shot1970s

Probably the tone of this era is best described by two words - Benny Hill. The politically incorrect comedian and countless other suburban sitcoms were having the fun over on ITV. In response, the BBC provided a stern alternative for proper, upstanding middle-class families in the form of Ask the Family. Families were also featured heavily in 1971's the Generation Game, which was to have its heyday in the mid 70s.

Bruce Forsyth welcomes his audience on The Generation Game

Bruce Forsyth welcomes his audience on The Generation GameThe turbulent political situation in the late 1970s, with strikes rife and the economy in freefall, gave Ted Rogers plenty of ammunition for his routines on 3-2-1. Here, amongst the very weak puns, you could see occasional glimpse of the kind of satirical humour that would eventually surface in the late 80s onwards.

Ted Rogers and Dusty Bin from 3-2-1

Ted Rogers and Dusty Bin from 3-2-1A further illustration of the strike culture is provided by an all-out strike at the BBC on 22nd December 1978. With no BBC to watch, everyone turned over to Sale of the Century, giving it 21.2 million viewers - the highest ever rating for an ITV game show.

Nicholas Parsons and friends on Sale of the Century

Nicholas Parsons and friends on Sale of the CenturyBeyond Gen Game and Sale, the other shows of the 70s were very much a mixed bag. The betting game Winner Takes All started in 1976, and the futuristic The Krypton Factor in 1977 (more of which in a moment). 1979 saw the light-hearted celeb fest Give Us a Clue while possibly the darkest show yet, Mastermind, went from strength to strength.

Magnus Magnusson in the Mastermind chair

Magnus Magnusson in the Mastermind chairProgrammes such as 3-2-1 (of Spanish origin) and the Generation Game (Dutch) marked a change in fortunes for the formats market. While scores of US formats had been replicated in Britain throughout the 50s and 60s, new European formats were beginning to score some successes here. Even the British had managed to make a trip across the Pond with The Krypton Factor - the first modern-style UK game show to be sold to the Americans. The economic conditions of the 1980s would see something of a recovery for go-for-the-throat American shows, but thereafter US formats would never find the UK market quite as easy to sell into.

Host of the Krypton Factor, Gordon Burns

Host of the Krypton Factor, Gordon BurnsEarly 1980s

School children of the 80s were being introduced to a range of new gaming influences, not least the mighty Dungeons and Dragons fad which in turn inspired arguably the first ever adventure game, called The Adventure Game, funnily enough.

The Drogna Game on The Adventure Game

The Drogna Game on The Adventure GameIn addition, computers were now finding their way into homes across the land. BBC Micros and Spectrums opened up new worlds in living rooms across the UK, and some producers spared no time using these same devices as ways of introducing a hi-tech element into their shows. Kids games like Finders Keepers, Beat the Teacher and First Class all made extensive use of microcomputers, and adult shows like Bob's Full House and Every Second Counts at least tried to look digital. Later in the decade, Knightmare - inspired by the computer game Atic Atac - broke through all kinds of technical barriers to bring a convincing dungeon to life.

The computerised game board of Bob's Full House

The computerised game board of Bob's Full HouseThe advances in technology also allowed larger-scale projects to become feasible. Long-range communications played their role in Top of the World and Treasure Hunt, and Ultra Quiz took contestants to places a UK game show had never been to before. Treasure Hunt - based on a French show - was probably the first ever action game show, and certainly the first to use helicopters.

Anneka Rice races for the clues in Treasure Hunt

Anneka Rice races for the clues in Treasure HuntPossibly in reaction to all the electronic gimmickry, the stubbornly manual Countdown launched the new Channel 4 into being. In possibly the worst case of overstaffing ever seen, no less than three different hostesses helped operate the card selection. One of these women, the now omnipresent Carol Vorderman, was hired on the basis of having "beauty and brains" and was originally credited as the show's "vital statistician", implying that hostesses were still being used as human wallpaper to an extent.

The launch of Channel 4 was more significant than the use of an extra button on the remote control. Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had decreed that Channel 4 were to make no programmes themselves - 100% of the output would be commissioned by Channel 4 but produced by independent production companies. It is largely because of this shift that companies such as Talkback, Celador and Hat Trick exist today.

1983 brought about a first in the shape of US import Blockbusters. The quiz was the first to run Monday through Friday. Many people said it wouldn't last. As it turned out, it has been revived more times than we can remember. This is partly due to its "charm" of having students as contestants. The US original and the pilot show originally featured adults.

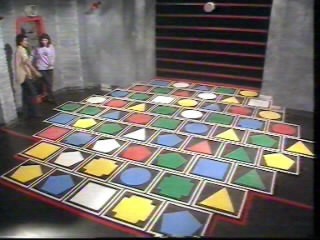

A game of Blockbusters in progress

A game of Blockbusters in progressMid 1980s

Let the good times roll. Mrs Thatcher's enterprise-led policies were bringing wealth to the middle classes and, despite high unemployment, money and goods were the aspiration of the time. This was reflected on television by the continued success of Family Fortunes and the introduction of an unabashedly consumerist version of The Price is Right. A series of privatisations brought about wider share ownership amongst the public, a theme capitalised on by The Stocks and Shares Show. The desperation that set in when the golden eggs began to dry up in the early 90s was reflected in the ruthlessness of Takeover Bid.

Leslie Crowther addresses the Price is Right crowd

Leslie Crowther addresses the Price is Right crowdAlthough money was everything in the 80s, in a sense money was merely a way of having a good time. The restrained nature of enjoyment that pervaded game shows to date was slowly disappearing, and emotions were becoming more exposed. American influences inspired a whole raft of shows where "the people were the stars". Practical jokes abounded in Game for a Laugh, while we saw relationships put to the test for the first time in the form of Blind Date. The UK had been bashful to pick up on the dating genre compared to other countries, which had had them years before.

Cilla Black sees where her contestants are going on their Blind Date

Cilla Black sees where her contestants are going on their Blind DateThe mid 80s also saw the re-birth of 'event' television. A trio of different Noel Edmonds-led formats (1, 2, 3) would steer BBC 1's Saturday night schedule until 1999. They were largely broadcast live, which was unusual in the era of videotape, giving them an "anything can happen" air of danger. They proved to be both ratings winners and the critics' embodiment of everything that was wrong with light entertainment.

Noel Edmonds holds a 'Gotcha' award

Noel Edmonds holds a 'Gotcha' awardSports shows generally had a timeless popularity. The Indoor League in the late 70s had shown darts on television for the first time (as well as bar skittles and shove ha'penny, but we'll gloss over those). A number of mid 80s shows revolved around indoor games, such as Pot the Question and the long-running darts game Bullseye.

Jim Bowen in front of the Round 1 dartboard on Bullseye.

Jim Bowen in front of the Round 1 dartboard on Bullseye.Late 1980s

1987 saw two somewhat desperate attempts by the monarchy to embrace the increasingly important role of television as a way of controlling opinion. Princess Anne was famously mistaken for a man a week before her appearance on A Question of Sport. However, the biscuit was well and truly taken by the crass mix of royal peerage, comedians and members of the public in large chef costumes that was the Grand Knockout Tournament. But it was all for charity, so that's all right then.

As the clamour grew over game shows filled with gags, girls and gunge, the call was answered in the form of ultra no-nonsense Fifteen-to-One. A professional, even stern, question master (namely, William G. Stewart, a former producer of Family Fortunes and The Price is Right) fires 120 questions per half-hour in a show where the game comes first and personalities hardly feature at all.

William G. Stewart in front of the final three contestants desk on 15 to 1

William G. Stewart in front of the final three contestants desk on 15 to 1The success of Trivial Pursuit and its ilk brought about a minor spate of puzzle games and board game conversions from the mid 80s to early 90s, including Television Scrabble, Cluedo and Trivial Pursuit itself. They drew the line at Operation, thankfully. Similarly, the increase in pub quizzes led to the phenomenon of the woolly-jumpered know-alls with wacky team names that have populated a constant stream of shows such as Masterteam, the Great British Quiz and on into the 2000s via The Syndicate and - most recently - Eggheads.

Political correctness was beginning to bite, not least in the title of one ITV game show called Everybody's Equal. Michael Barrymore's startling style of presenting brought a new dimension to the small screen, and the contestants on his Strike it Lucky show came from a wider range of backgrounds than the typical white, middle-class husband-and-wife teams seen in the 70s.

And while US import Wheel of Fortune reinforced the stereotype of the Barbie Doll hostess in some ways, the introduction of "Prize Guys" demonstrators and the first black hostess that we can remember went some way to contribute to the political correctness of the age.

Early 1990s

Podia and placards made way for big budget studio extravaganzas of varying degrees of success, mainly due to European influences. You Bet! continued to show members of the public performing extraordinary stunts. Channel 4's top-rating The Crystal Maze proved that fantasy locations could work, just so long as you had a few million quid to spare. Attempts by other channels to copy its success fared less well. The BBC got their fingers burnt with Happy Families, while ITV's attempts to portray a spaceship overrun by aliens in Scavengers bordered on farcical despite significant investment from US network Fox.

Richard O'Brien charts a course through the Crystal Maze

Richard O'Brien charts a course through the Crystal MazeLarge-scale kids shows were having more success. The glam rock-inspired Cheggers Plays Pop in the late 70s had given kids an early slice of inflatable, foam-filled fun. Fun House and Finders Keepers took the concept further with a couple of genuinely impressive large-scale sets. The common theme in these shows was "There are no parents around to stop you".

Pat Sharp in front of the Fun House

Pat Sharp in front of the Fun HouseHowever, in adult light entertainment the ideas well was beginning to run dry. Certainly no-one knew what to do with Saturday nights so the schedules throughout the 90s remained virtually untouched, with the Big Break, Blind Date and company all getting long runs. Long-dead shows such as the Generation Game, the The 64,000 Dollar Question and Celebrity Squares were dusted off from the back of the formats cupboard. While these remakes pulled in respectable ratings, most couldn't replicate the success or longevity of their initial incarnations.

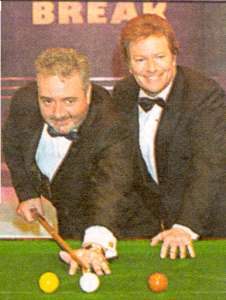

John and Jim cue up for a quick frame on Big Break

John and Jim cue up for a quick frame on Big BreakAs we've already seen, whenever there is a glut of shows that rely on ostentation there's usually a show that reacts to the fad. In this decade this came in the form of Have I Got News for You, which consisted of five people sitting behind a desk with only a newspaper decoupage for set dressing (a meagre electronic scoreboard was a later concession). The comedy panel game had been given a harder edge, and launched a number of copycats in various fields. Shows based on wide topics - such as sport and music - fared well. Shows on specific topics - such as science fiction, advertising and the bizarre - bombed.

Angus Deayton, host of Have I Got News for You

Angus Deayton, host of Have I Got News for YouThe difficult geography of British housing made the installation of television cables a pipe dream compared to the wide streets and large cities of the USA. This, combined with a bitter competition battle between two rival satellite systems (BSB and Sky) meant that few viewers were watching non-terrestrial programmes. Those that were had only bought-in repeats and revived versions of old hits like Blockbusters and Sale of the Century for company.

Mid 1990s

Hey! The UK may be in the middle of a recession, but that doesn't stop funsters such as Noel Edmonds, Chris Evans and - er - Gaby Roslin offering punters a range of life-changing experiences and "money can't buy"-type prizes on Noel's House Party, Don't Forget Your Toothbrush and Whatever You Want respectively.

Chris Evans with his Toothbrush. Don't forget it.

Chris Evans with his Toothbrush. Don't forget it.The regulators saw sense and removed the extremely artificial limits that restricted the value of prizes that could be given away on game shows. From 1 January 1993, producers were no longer restrained by the £6000 prize cap imposed by the 1981 Broadcasting Act and could really start to splash the cash. With house prices at a post-80s low and negative equity rife throughout Middle England, Raise the Roof offered the golden dream of a free £100,000 house. Shame the game wasn't any good.

Bob Holness makes his grand entrance on the set of Raise the Roof.

Bob Holness makes his grand entrance on the set of Raise the Roof.Cyberzone and Virtually Impossible proved that the world's still not ready for virtual reality sets. It's the future of game shows, apparently, but we're still waiting...

Confessions got Auntie Beeb into trouble for daring to reward wrongdoers, but the fad for psychological dilemmas had already started in the late 80s with Scruples and PSI. The trend continued with Do the Right Thing, and began to turn really nasty later in the decade with Can We Still be Friends? and its follow-up Ex-Rated.

The bar for what contestants were expected to put their bodies through was significantly raised. Previously, the most a contestant could expect to sweat through was the assault course round on the otherwise largely cerebral The Krypton Factor. Interceptor saw contestants being chased around the British countryside and, from the same producers, The Crystal Maze in 1990 got contestants running around the studio, and from 1992 an impressively executed version of Gladiators (from a much lower-budget US show American Gladiators) got the nation on tenterhooks as contestants bounced on bungee ropes and hit each other with oversized cotton buds. Now Body Heat - a game show dedicated to the topic of physical fitness - arrived on the scene to ensure those sweat bands didn't dry up.

The set of Body Heat

The set of Body HeatLate 1990s

Although this was to be something of a new golden age for UK game shows, it began with another minor crisis of confidence in the entertainment commissioning departments. Traditional light entertainment slots were being dropped in favour of new "docusoap" series, so whatever shows that did receive commissions had to be sure-fire hits - or at least, good enough not to flop. Why risk new shows when you can dust off old ones? Sure, the ratings might not be fantastic, but at least they would be respectable enough. The best of these revivals were Blankety Blank and, in an afternoon slot, Call My Bluff.

In a similar vein, everyone was trying to come up with the new Opportunity Knocks at the time, which was strange because the Beeb itself had only given it a second airing - this time with game show veteran Bob Monkhouse at the helm - back in 1987. A spate of variety formats began with Pot of Gold and continued with Jonathan Ross's The Big Big Talent Show, Get Your Act Together and Star for a Night. The only format with any real legs was singing impressions show Stars in Their Eyes, another widely successful European format.

A George Michael impersonator on Stars in Their Eyes

A George Michael impersonator on Stars in Their Eyes1997 saw a couple of very important developments. For the first time in 15 years a new terrestrial channel - Channel 5 - was launched. An unfortunate bandwidth clash with the existing frequency used by most video recorders in the UK and a lack of transmitter power severely limited the potential uptake in the early months. Even three years later many people in the countryside (including some of the channel's own senior staff) still couldn't receive the station. Channel 5's minuscule programme budget (a tenth of their main rivals) required a new way of thinking to make the money go around. This was perfectly embodied by 100%, a programme of almost breathtaking minimalism. It was a comparative success.

A game of 100% in progress

A game of 100% in progress1997 also saw the conversion of the über-generically titled cable station The Family Channel into the honest-to-goodness Challenge TV we have today. The Family Channel had always run a near-continuous diet of game show repeats, but it had never been targeted as a channel for game show fans as such. The channel began commissioning shows of its own - such as new versions of Winner Takes All and Sale of the Century (yet again), and a localised conversion of the Japanese torture show Endurance UK - as a way of pulling in the crowds. It's still an upward struggle for the channel, but increased original programming has recently been promised.

Endurance UK's Paul Ross (centre) with Hoki and Koki

Endurance UK's Paul Ross (centre) with Hoki and KokiThe lifestyle game show comes to town. Not content with filling their daytime schedules with cookery shows, gardening shows, makeover shows and seemingly nothing else, the BBC rolled out a number of game shows based on these same lifestyle activities. The grand daddy of them all was actually the primetime BBC 1 show Masterchef back in the early 90s, but it was the success of Fern Britton's Ready Steady Cook that in turn gave rise to Can't Cook, Won't Cook, Anything You Can Cook..., and Mixing It. The former sobriety of the Antiques Roadshow on BBC 1's Sunday nights had to make way for the jolly hockey-sticks approach of The Great Antiques Hunt, later done on the cheap as Going, Going, Gone and Bargain Hunt. Houses also got into the act, with Whose House? and the decidedly specious Better Homes satisfying the UK's new lust for DIY. Incidentally, just one independent production company - Bazal Productions - made the majority of the advances in this genre.

Fern Britton on the set of Ready, Steady, Cook

Fern Britton on the set of Ready, Steady, CookWhen all the topics under the sun had been used up, a while later "cross-genre" shows would start to appear. Trading Up asked people to match cars with personalities, while Dishes combined a dating show with a cookery programme.

Claudia Winkleman sitting on top of a car bonnet for a publicity photo for Trading Up

Claudia Winkleman sitting on top of a car bonnet for a publicity photo for Trading UpAs you'll have noticed by the amount of text in this section, the late 1990s were a period of some major changes to the way that people watched television. Thanks largely to the X-Files and the Simpsons on Sky One, take up of non-terrestrial channels were now reaching respectable (but still small) audiences. But with resources becoming more stretched programme budgets fell, which was bad news for period drama but good news for game shows which could record up to 6 programmes a day. Additionally, game shows had not waned in their ability to pull in good ratings - particularly as a way of "warming up" the audience for programmes later in the evening.

This pace was not going to slow down in 1998, as a little show called Who Wants to be a Millionaire? arrived on the scene. The formerly unheard-of practice of clearing out a major network schedule for a two-week period worked wonders, as ratings not seen since the 1980s built up an impressive head of steam for ITV.

Chris Tarrant hosted the original Millionaire

Chris Tarrant hosted the original MillionaireThe impact of Millionaire was huge. All of a sudden, everyone in the formats market wanted to talk to anyone with a British accent. The Far East were also enjoying a few successes, with shows such as The Moment of Truth - based on a Japanese format called Happy Family Plan. Even the mighty Americans - formerly a little precious in their "Land of the Game Show" label - had to admit that they had become somewhat stuck in their ways. A new era of game show mania had begun, and you'd be forgiven for thinking we were back in 1957.

Millionaire was a nightmare for the BBC. They didn't have millions of pounds to give away, since most of their prizes come out of the 'licence fee' - effectively, a tax of approx. £100 payable by everyone in the country that owns a television. It is the lifeblood of the BBC (in return, the BBC promise unique programming not provided for by commercial channels) and it couldn't be frittered away in quiz prizes. So instead they had to be clever and find another jeopardy. After piloting a higher-than-usual number of formats, they found hits in Friends Like These and, later, The Weakest Link. Here, the currency used was personal alliances - and they're much cheaper than cash. Tapping into the same kind of vibe around the same time, but with less success, were Grudge Match and Wanted.

The loyal "technobods" audience - which hadn't been serviced since The Great Egg Race in the 70s/80s - suddenly found a plethora of science shows to enjoy. The two most successful were Robot Wars (an American event idea televised first in the UK), and Scrapheap Challenge (very similar in concept to Great Egg, but larger in scale).

Two Robot Wars contestants

Two Robot Wars contestantsOne of the last acts of John Major's Conservative government was the introduction of the UK's first national lottery. The BBC had won the licence to broadcast the live draw, the idea being that millions would flock to the channel when the numbers were being drawn. While that was true to an extent, the draw itself only took minutes whereas rating figures require that a viewer stay with a programme for a minimum of 15 minutes. Therefore, a variety of formats were devised to pad out the proceedings, including a fair share of game shows.

The first attempt, the The National Lottery Big Ticket, was an attempt to make a version of the successful lottery shows with large-scale games seen in Germany and Holland, but strict UK gambling laws and concern from the BBC's governors effectively crippled the show. Channel 4 tried to get in on the act with Last Chance Lottery with some success. Of the various formats tried, Winning Lines has probably been the most successful so far. After finding its feet with some good new formats to go into the new millennium, the BBC went and spoiled it all by commissioning another lottery vehicle, the disastrous mix that was Red Alert.

Simon Mayo and his swivelling computer on Winning Lines

Simon Mayo and his swivelling computer on Winning LinesPretty much every taboo had been ticked off the list between 1990 and 2000. There'd been a quiz show about sex (Carnal Knowledge), religion (Heaven Knows), two featuring full nudity (series Naked Elvis and naturism special Naked Jungle) and even one about death - although that was a satirical one-off for a theme night of health programmes.

As Channel 4 reached its 18th birthday, it had come of age in more ways than one. Now increasingly looking more like a mainstream channel, it became somewhat less adventurous. Traditional game shows were not its strong suit in any case, so it was left to Channel 5 to take more risks in the way that Channel 4 once did. Back in 1998, they cheekily commissioned Fort Boyard, the series that actually inspired Channel 4's former hit The Crystal Maze, and continued to enjoy success with it into the 2000s.

Melinda Messenger in the tarantula room on Fort Boyard

Melinda Messenger in the tarantula room on Fort BoyardEarly 2000s

"24/7" formats such as Big Brother, Survivor and The Mole were scoring big successes in Europe and were beginning to make their mark in the UK and US. Again, Channel 5 showed it wasn't afraid of taking risks by building a whole prison for Jailbreak - shame virtually no-one watched it. Big Brother proved to be the first largely successful implementation of a format using simultaneous Internet streaming and content, with other interactive ideas such as The People Versus looking to extend the theme. Meanwhile, with Bare Necessities, the BBC gave the outward-bound sub-genre its first airing since the pioneering Now Get Out of That in the early 80s.

Davina McCall, host of Big Brother in the UK

Davina McCall, host of Big Brother in the UKAs the level of docusoaps had reached overdose, some of the light entertainment slots began to come back into the schedules. In fact, the time-slots had a distinctly 1980s feel, with a traditional Monday 7pm quiz on both BBC 1 and ITV (The Syndicate and The Price is Right) for the first time since the demise of Telly Addicts and the The Krypton Factor. The regular BBC lunchtime quizzes (Quotation Marks, Playing for Time etc.) were also back in force, and the "cheap as chips" daytime show Bargain Hunt not only became a sleeper hit but also inspired a whole genre of copycats.

The Syndicate recreating the Bohemian Rhapsody music video

The Syndicate recreating the Bohemian Rhapsody music videoAt the other end of the scale, there was a slew of programmes which demanded more of their participants than ever before. Both Touch the Truck (Channel 5) and Shattered (Channel 4) played with sleep deprivation, Sky One's Fear Factor tested nerve and physical endurance, while the BBC weighed in with SAS: Are You Tough Enough?, arguably the most demanding British game show ever, and Spy, where uncertainty and paranoia were built into the format.

Dale Winton touching a truck. See what we did there?

Dale Winton touching a truck. See what we did there?The big success story of this era was undoubtedly the return of the talent show, now crossed with the reality genre to create ITV's trilogy of Saturday night hits Popstars, Pop Idol and Popstars: The Rivals. Even the BBC got in on the act, with Fame Academy being a hit almost in spite of itself.

Mid 2000s

By 2005 or so, game shows seemed to be in a bit of a slump. The last few years had seen ITV practically axe every gameshow they had, even ones that had been running for over 20 years, and in their place came a whole string of high-profile flops: Public Property, Shafted and I'm the Answer were axed in mid-run, while the likes of The People Versus and 24 Hour Quiz played out to dismally low ratings. Even recent hits such as Millionaire? and Link weren't pulling in anywhere near the number of viewers they used to, and while there were some bright sparks among the dirge of phone-in quiz channels, things were undeniably not as good as they were at the start of the decade. Saturday night shows continued to pull in the punters, with Strictly Come Dancing, The X Factor, the ubiquitous Millionaire and even In It to Win It doing brisk trade, but elsewhere the hits were few and far between, with I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! being the exception that proved the rule.

So it was somewhat of a relief for Deal or No Deal to arrive and become the first new game show in years to actually get everyone talking. It had a £250,000 top prize, something that would have been inconceivable 10 years earlier in primetime, let alone daytime, and the welcome comeback for gameshow god Noel Edmonds. This coupled with the success of Ant and Dec's Gameshow Marathon seemed to revitalise interest in the genre, and subsequently many old favourites (Bullseye, The Price is Right, Family Fortunes) re-appeared on our screens.

Performance shows went from strength to strength, with Simon Cowell responsible for the two biggest - The X Factor and Britain's Got Talent. Meanwhile, the BBC had a big hit with musical theatre talent search How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria? and followed it up with Any Dream Will Do and I'd Do Anything. Celebrity performance shows fared well too, with ITV's Soapstar Superstar and Dancing on Ice and the BBC's Comic Relief tie-in Let's Dance, while Strictly Come Dancing went from strength to strength. More unusual applications of the concept included celebrity orchestra conducting in Maestro, celebrity showjumping in Only Fools On Horses and celebrity dog training in The Underdog Show.

One surprising trend was the growth of shows dealing with the world of business. The Apprentice, a format imported from the USA, proved successful enough to transfer from BBC Two to BBC One, leaving the junior channel with the more upmarket Dragons' Den and the curious hybrid The Restaurant.

Future

As we head along the road, there's no doubt that the progress of game shows is onward, but which direction they'll take is anybody's guess. The trend for taking a tough line on contestants seems to have passed for now, but it will surely be back in some form, sooner or later. In the meantime, by getting back to the basic proposition of having a jolly good time, the game show has gone from strength to strength and shows every indication of continuing to do so for a long time to come.

The Countdown dream team -

The Countdown dream team -