Weaver's Week 2021-07-18

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Contents |

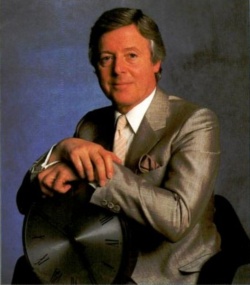

Michael Aspel

So far, our career profile of Michael Aspel has concentrated on his television work. Crackerjack, Miss World, Give Us a Clue, and more. But television was only one string to his bow.

Michael always had time for radio. He was one of five regular hosts for After Seven on Radio 2 in 1971, a programme of light music and good company for the early evenings. The other hosts: David Jacobs, Michael Parkinson, Ray Moore, Robin Day. A Saturday edition of The Today Show gave Radio 4 listeners tips on gardening and cookery, something John Humphrys would benefit from.

Michael moved to Capital Radio in autumn 1974. By the standards of the time, Michael's style was relaxed and informal, welcoming each listener into his parlour for a cup of tea and a gentle conversation. He didn't attempt to build worlds like Noel Edmonds, he didn't act the fool like Kenny Everett, he didn't even attempt the whimsy of Terry Wogan. Michael Aspel was solid and asked for nothing more than your company.

After ten years as the housewives' choice, time and changing fashions caught up with Michael Aspel. He'd finished the daily show on Capital in summer 1984, and saw out his contract with a weekend show until the end of the year. Michael's golden tonsils had made him the perfect choice for In-Flight Radio from 1979, gentle and familiar narration to match gentle and familiar tracks on those long flights.

Michael had been named as a possible replacement for Terry Wogan on Radio 2 at the end of 1984 – others in the frame included Tony Blackburn and Russell Harty, but these guesses were a long way off the mark – Ken Bruce got the job. He was considered for Desert Island Discs when Roy Plomley suddenly died in 1985, but was passed over for Michael Parkinson from Give Us a Clue.

Instead, he worked on LBC in autumn 1987, hosting a weekend speech programme reflecting life – very different from the station's weekday hard news programmes. He also hosted a nostalgic show on Saturday morning Radio 2, a slot quickly bequeathed to the rambunctious feminism and sharp music of Anne Robinson. Michael had a longer run on Radio 2 Sunday mornings from 1994-6, and hosted Radio 2's documentary clip series Auntie's Family Album in late 1997, asking broadcasters about their favourite snapshots of radio.

It's Friday, it's six o'clock

Michael remained an integral part of London's television screens, from 1982 as the host of LWT's energetic start to the weekend, The Six O'Clock Show. For boring franchise reasons, The Six O'Clock Show included the day's news, but then had 35 minutes of topical comment. The show visited your part of London, and told the story of your village, or covered your strange event. The flower and vegetable show in Lambeth? Grist to the mill, especially the plotting in the potting sheds. The fashion of recording your wedding on a home video? Of course they'll cover such a people story, especially with video bloopers to show.

Segments were presented by a mixture of the offbeat (Fred Housego with the travel news in a helicopter, Chris Tarrant larking about outside the studio), the dad-friendly (Paula Yates, Samantha Fox), and the hip (Janet Street-Porter talking about school reports, Danny Baker meets some people wearing Walkmans). The segments were directed by sharp talents such as Liddy Oldroyd, Paul Ross, Paddy Haycocks, and Sue McMahon.

Once again, Michael Aspel calmly held the show together, joining in with whatever mayhem was being visited by the young whippersnappers, like a benevolent uncle indulging his relatives' whims. He gave a short series of topical jokes near the start of the show, and read out some of the week's funnier stories near the end. Before the series started, there was much muttering that Michael was the second choice after Terry Wogan; Michael made the show his own. It was the brainchild of Greg Dyke, and formed the nucleus of his later rescue of TV-am. For The Six O'Clock Show, Michael won the Television and Radio Industry Club award for ITV personality of the year in 1984.

The Six O'Clock Show finished in summer 1988, as LWT were asked to enhance their local news output otherwise they might not retain the broadcasting contract.

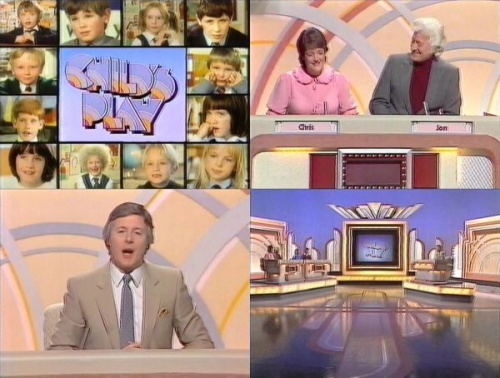

Child's Play

Michael made other shows for LWT, including this primetime show. Child's Play had a simple idea, get children to talk about something, and see if the adults can keep up.

Like every ITV primetime show, it's a mixture of the public and celebrities. Here, we have Jon Pertwee from Worzel Gummage and his lady contestant. And we have Isla Blair and her gentleman contestant. All of the panel have children, and all talk about their offspring in the introduction. (Michael has six children of his own, but doesn't talk about them so much.)

After a few minutes, we're into the game proper. Round one asks the teams to guess a word the children are talking about. 15 points for a guess on one clue, fail and it goes to the other team for 10 points. Fail again and it's back to the original team for 5 points, and if you miss that Michael will tell the answer. The clues get easier as the round progresses. Order of play is man-man-woman-woman across teams, with no conferring at this stage. Each player will start with the first guess at a word.

Round two, written definitions from the children. One member of the team (usually the contestant, not the celebrity) faces this challenge. Michael reads the clues, our player is to guess. 10 points per right answer; a good player can easily score 50 in the 45 seconds allowed.

The commercial break comes next. Child's Play benefits from a bouncy theme by Laurie Holloway, written to sound like juvenile fun. The set is pastel orange and grey and built in a sort of art deco style. For most of the game, answers are shown on screen so we can look away and play along – if we're quick!

Round three is the "bonus round", lots of definitions come in a montage of children – some are helpful, some are not. A whopping 50 points per right answer, offered to the other side if needed. One question for each team.

Buzzers have appeared during the commercial break, they're used in the "fast play" final round. Buzz in to stop the clip and give the word the child is defining. 20 points per right answer, one guess per team.

The prizes are small. Loser gets the Child's Play trophy, a sculpture in the show's logo, made of some silver metal. Winner gets an identical trophy, and a hamper full of goodies.

At the time, Child's Play received good reviews, it's the first time anyone has tried a show like this, taking little bits of film and editing them together to make a sensible game. Apparently, they shot 31 miles of film for the first series, which must be a lot to catalogue and edit. The show was computer-controlled, as the tape operators never knew when an answer would be guessed – and something had to stop the tape as soon as the buzzer was pushed. Like Ultra Quiz the year before, Child's Play was gently pushing the limits of available technology.

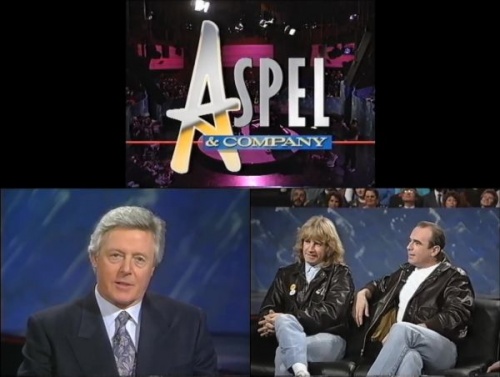

Aspel and Company

When we summarise Michael Aspel's career in one word, "dependable" would be it. The general public might say "chat show host". His long-running chat show Aspel and Company was an undemanding watch. It was aimed squarely at the middle-class audience who wouldn't normally watch ITV because they thought commercials were beneath them. Aspel and Company invited guests who were already known – regulars included Victoria Wood, Tom Jones, Maureen Lipman, Joan Collins.

LWT were criticised in 1984, when an interview with then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher generated enthusiastic applause, even though the audience was never shown. LWT promised that these were genuine reactions, if anything toned down so as not to drown out the guest. It's the ultimate irony: a live audience sounding more fake than Canned Crowd™.

Turned out that the kind of people who spend months on the waiting list for tickets to see the Michael Aspel chat show are there to see Michael Aspel, and do not feel so strongly about politics. Most of them come from Womens' Institutes and mothers' unions; many would have been more excited by the week's other guest, Barry Manilow singing "When October goes".

One live edition turned into an advertisement for the Planet Hollywood restaurant opening in London. The business owners – Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Bruce Willis – guested on Aspel and Company, and twisted every question to promote their venture. After some consideration, and fair criticism from the regulator, Michael chose to wind down his chat show. Guests needed to be honest and spontaneous; too often, they were rehearsed to their soundbites. Michael hosted a clip show on New Year's Eve 1993, and that might mark the end of the genre as it was known in the 70s and 80s. The field was open for newcomers with different ideas: Jonathan Ross, Graham Norton, and others.

Michael's career continued in a pleasant manner. His gravitas gave him the host's job on Emergency 999 in summer 1987, following police, ambulance, and firefighters over a weekend. Four regional broadcasters were multiplexed together in Southampton and hosted by Michael Aspel at the BT Tower in London. This turned out to be a dry run for the planned ITV Telethon, and Michael's experience and popularity meant he was a natural host.

The ITV Telethon was a massive charity appeal that took over the whole network for 27 hours in May 1988 and May 1990, and again in July 1992. Michael was in the studio as Treasure Hunt played through the country, as company spokespeople presented their oversized cheques, as Ross King introduced an early look at the Young Krypton course, and we got very familiar with the ITV regions. And masses of money was raised for great causes.

Later in 1988, Michael took on another job, again following in the footsteps of Eamonn Andrews.

This is Your Life

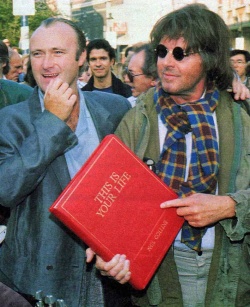

When we think about it, This is Your Life is such an obvious idea. Guests are surprised with a presentation of their personal history. Created for NBC by Ralph Edwards, This Is Your Life ran with Eamonn Andrews from 1955 to 1964, and again from 1969 until his death in 1987. Michael Aspel – who had been "lifed" himself in 1980 – took over as host.

While the NBC version often featured unknown members of the public, the BBC and Thames take on This Is Your Life was always about a celebrity. It's a way to get to know someone better, to humanise them and share some of the things important in their life. A slickly-edited show, it covers a lot of ground and introduces a lot of people in a very short time. And there's always a lot of showbiz glitter, famous faces who we might like.

Each show followed a familiar template. We join Michael behind the scenes at some showbiz event, perhaps in disguise. The week's subject has no clue that they're going to be featured, and the surprise is genuine – and always caught by cameras.

The host reads a linking narrative, and there are brief reminiscences by relatives and friends. We start with close family – siblings, parents, spouse, children. Then we branch out to people from the personal life, and the professional life. A voice, of someone "who you haven't seen for twenty years!", before that person walks on to set. Those colleagues who can't be with us tonight might send a short video tribute. As the show progresses, more and more people crowd into the studio.

The programme ends with a huge parade of well-wishers, before Michael gives the star of the show one final gift – a red book, which carries all the information in a red book, which is given to the celebrity as a memento of their surprise party. This is Your Life had plenty of schmaltz and sentimentality, and we viewers were brought into the action through a barely-edited recording of the live event.

By now, it's clear that Michael Aspel's talent is in letting other people shine. He's the catalyst, a safe pair of hands. Michael Aspel won't offend, he won't overshadow the guest or the star. He's the human embodiment of the Radio Times: sensible, well-written, literate, discerning.

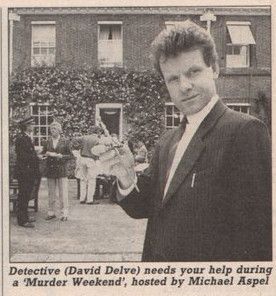

A murder is announced

Michael was occasionally involved in some slightly paranormal practices. He'd presided over Star Signs, a panel show revolving around astrology and attempts to tell the future based on the apparent movements of stars and planets. He'd hosted Strange But True, an investigation into unexplained phenomena, such as unidentified flying objects, the Loch Ness monster, and just how British Rail manage to make their sandwiches so tooth-crackingly hard.

And, in 1989, Michael was present at a murder. There was much love between the Earl's second son and his betrothed. The couple's families didn't share that ardour, and there was a series of killings throughout the weekend. Such was the plot of Murder Weekend, where 24 amateur sleuths tried to unmask the one true killer.

Joy Swift had created the murder weekend genre in the early 80s, and wrote the plot for this event. Unfortunately, what works in real life doesn't always transfer well to television. The cast were experienced television actors, able to look good on screen; they weren't experienced with the specific and unusual demands of a murder weekend. Our actors aren't just playing for the camera, but for these 24 amateur sleuths following their every move.

There were logistical problems, too: the show stuck closely to the traditional murder weekend schedule, with events happening as they happened. Nothing was staged for the cameras, and the 24 amateur sleuths had a nasty habit of crowding out the cameras so we couldn't see what they see. The producers had some new hand-held cameras, but chose not to use them for these scenes. The producers chose to concentrate on the main plot of the warring families, rather than try to keep up with the ideas from any of the 24 amateur sleuths.

Viewers were invited to play along at home, and call in with their prime suspect and motive. Some of the best viewers' suggestions earned them a trip to see the denouement for themselves. But, again, a lack of planning meant this element misfired: the TV Times refused to print a supplement giving extra clues, and confined itself to potted biographies of the characters.

The finale was another oversight: the main episodes had been filmed some weeks prior, and both the actors and Michael Aspel had forgotten some of the intricate details of the plot. While viewing figures were more than respectable, the show had gone badly over budget, and wasn't recommissioned. It wasn't until 2020 that another Celebrity Murder Mystery took place, this time on Channel 5 – and sensibly pre-recorded.

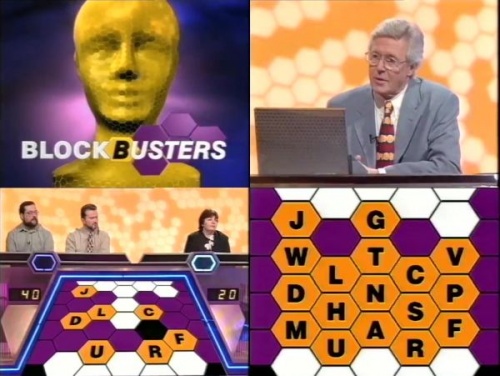

That's Blockbusters

Michael's career took him back to the BBC, first on Radio 2 weekends, and then when This is Your Life went across on a Bosman transfer. He hosted The Announcers' Challenge, allowing the continuity staff on Radios 2, 3, and 4 to make fools of themselves.

By Easter 1997, Michael was firmly ensconced at the BBC. He was the choice to host an unexpected revival of everyone's favourite hexagon quiz. Blockbusters began in a sea of publicity on Easter Monday 1997, it would turn out to be the day's second-biggest debut behind Teletubbies.

Michael followed in the footsteps of an all-time television legend. Bob Holness had hosted Blockbusters on ITV for over a decade, and it was only a few years since his last episodes had been seen. To many viewers, Bob was an integral part of the show, and anyone different wasn't going to be good enough.

Other production decisions didn't work in Michael's favour. The theme music was not quite "Quiz wizard", but a very close approximation of Ed Welch's work. Either license the original, or give us something very different, because this comes across as cheap. They'd also decided to increase the age range – Blockbusters was no longer for sixth-form students, but for students of all ages. It's a tenuous link, and after the first few episodes they dropped the "student" idea anyway. Three Gold Run prizes before a team or player retires undefeated.

And Michael calls them "hexels" not "hexagons". And the two-player team is playing in purple rather than blue. And the consolation prize isn't a dictionary or organiser but a fountain pen. And the studio arrangements are an exact mirror of Central's classic layout – the board's on the right, the solo player is sat on the right of the playing desk. It's a lot of little changes, as if they wanted to make the show as different as they could from ITV Blockbusters without changing anything.

Michael Aspel starts a little stiff and wooden, but soon relaxes into his role – ask the questions, chivvy along, keep spirits up. Like Bob Holness, Michael's got a natural empathy, people seem to want to shine to him. And truth to tell, if we'd never seen Blockbusters before, this would have been a perfectly acceptable show. The problem was that we had seen Blockbusters before, and this was different, and Michael isn't Bob.

The consolation prize, a contestant tries for the Gold Run, and the top prize is a trip to Reykjavik.

The consolation prize, a contestant tries for the Gold Run, and the top prize is a trip to Reykjavik.

To be fair, BBC daytime was going through formats like a knife through butter. In 1997 alone, they had the evergreen Today's the Day and Ready Steady Cook, and a whole slew of other shows. Can't Cook, Won't Cook, The Alphabet Game, Going for a Song, Going, Going, Gone, Call My Bluff, and Give Us a Clue. Lots of antiques, lots of familiar shows from the past. Blockbusters was just one amongst many new old shows. No surprise that it wasn't renewed for a second series.

We mentioned Going for a Song up there. Michael hosted a few series of that as well, it dovetailed with his job on the Antiques Roadshow. It proved to be the perfect job for Michael, he chats with the people, he's inquisitive, and he brings out the best in everyone he meets. During his time on Antiques Roadshow, Michael turned down the host's job on Countdown; Richard Whiteley's shoes were too big for anyone to fill immediately. Michael left Antiques Roadshow in 2008, and has enjoyed his retirement since.

Throughout his career, Michael Aspel was always self-effacing. He was a familiar face, able to charm and reassure in equal measure. Unlike so many other stars, we didn't really get to know the man behind the charm; he was a smooth and calm presence. We learned more about the guests on his chat show, the contestants on his games, than the man himself.

Michael Aspel never took the limelight, but reflects it onto his guests. He had mastered the prosaic art of live broadcasting, and then used his skills to tell the poetry of people's lives.

In other news

Just an ordinary day at UKGS Towers, finding silly pictures of Danny Baker, clipping Christmas pudding recipes and sending them to our mate in the snow. And chatting with our chums in the Channel 4 press office.

- Anything else on Channel 4?

- I literally just told you.

- That doesn't answer the question. What's new on Channel 4?

- I literally just told you.

- Sorry, are you the publicist?

- Yes.

- And you want us to publicise your show?

- Yes.

- And you don't know the show's names?

- Yes, I literally just told you.

- Well go ahead and tell me.

- I literally just told you.

- OK, let me get the schedule accurate. So tell me, what's on first?

- No, who's on first. What's on second.

- What's on second?

- Yes, and who's on first.

- Thanks, Bud.

I Literally Just Told You asks contestants to remember what happened in the last few minutes. It's another format by Richard Bacon (This is My House, The Hustler) for Expectation Entertainment, and it's hosted by Jimmy Carr. Richard Bacon's quoted, "The heart of the idea is we write the questions as the show is happening. So when the show starts, at least half the questions in the show have not been written and we write it based on what happens live."

Radio 4's Brain of Brains took place this week, the challenge for recent champions. Sadly, 2018 champ Clive Dunning couldn't join the recording, but successors Graham Barker and David Stainer could. They were joined by high-scoring runners-up Frankie Fanko and Hugh Brady.

"A rumour swept the internet that the flavour vanilla is extracted from the anus of which animal?" They wouldn't have asked this in Robert Robinson's day. David Stainer took a small lead after the first round. All players claimed a bonus in the second round, only David took a question of his own. Frankie Fanko overcame some of the gap in the next round. Beat the Brains followed, with a set chosen for the occasion.

There's not much movement in the next round, Hugh Brady loses more than anyone gains. Frankie scores four on her own questions in the final round, but it's not quite enough. David wins the contest with 12 points, Frankie has 11, Graham Barker 10, and Hugh 8. It was the bonuses that won it: David scored just four on his own questions, and swooped for eight on other people's errors. Frankie had the knowledge, 10 correct answers on her assigned stumpers. A full series of BBC Brain begins on Monday, the final is scheduled for 8 November. David Stainer returns on the next Top Brain, likely to air in October 2027.

We wondered if there might be a Topical Insert into this week's Only Connect. There was a topical insert into this week's Only Connect, a disallowed goal just before the final whistle, and then a Super Over to decide the winner. Librarians won the breaker, beating the Scrubs after an 18-18 draw. No tiebreaker on University Challenge, King's College London beat Glasgow by 115-100.

Why such an early start for Only Connect? We suspect it's to fit around the sports. The Winter Olympics are happening next February, and 28 episodes (plus a week off for Boxing Day) takes us to 31 January. The sports start the following weekend.

Where is Mastermind? Assuming it's staying at 7.30 on Monday. we reckon it'll begin after the international cricket season has finished, so 20 September looks likely. Wouldn't be surprised if they again double up on episodes during the spring.

A reader asks, "Is The Hundred a game show?" It's a made-for-television event, loosely based on the traditional game of cricket. It's spontaneous and unscripted, with a clear competition and rules. But is it a sport? Would this event attract a paying crowd if it weren't on television? We think it would, certainly the promoters hope that it will get people into the cricket grounds. While it ain't cricket, it's clear The Hundred ain't a game show.

The Television and Radio Industries Club have announced nominations for their annual awards. Who have we got:

- TV Personality – Alison Hammond, Ant & Dec, Bradley Walsh

- Food Programme – Bake Off (and two others)

- Entertainment Programme – Saturday Night Takeaway, Bradley Walsh and Son Breaking Dad, Gogglebox

- Comedy Programme – Would I Lie to You (and two others)

- Reality Programme – I'm a Celebrity, The Masked Singer, Strictly Come Dancing

- Sports Programme – A League of Their Own, A Question of Sport, Match of the Day

- Daytime Programme – The Chase (and two others, including Steph's Packed Lunch)

A quiet week for new shows, though BBC3 provides something to tickle our fancy. The Rap Game begins a new series (BBC1, Thu), and Fast Food Face Off is a one-shot (BBC1 NI Mon, elsewhere Tue). Next Saturday has some big things on BBC1: a full series of Take Off with Bradley and Holly, and the second series of television's greatest theme tune The Wheel.

Pictures: LWT, Capital Radio, Thames, TV Times, Fremantle (UK), BBC, Bear Grylls Ventures / Electus / betty.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.